Why this information is important

Climate change and climate variability have already challenged Western Australian (WA) broadacre cropping and animal production. Producers have been able to meet these challenges by adopting innovative farming systems to maintain farm productivity and profitability. Future climate change will present further opportunities and challenges for producers.

Records show that rainfall decreased and temperatures increased over the last century. Climate projections for the south-west of WA are for declining rainfall and higher temperatures.

The grainbelt of WA contributes more than $4.5 billion to WA’s economy per year. Kojonup is 250 kilometres south-east of Perth on the western edge of the southern grainbelt. This agri-climate profile provides a historical analysis and projections for a range of climate variables relevant to farm businesses in the Kojonup area.

Changes at a glance

Around the mid-1970s there was a shift to consistently drier winter conditions in south-west WA. Kojonup has experienced an 8% decrease in annual rainfall and a 10% decrease in growing season rainfall (April–October) from 1931–1974 to 1975–2018.

The observed trends in Kojonup’s climate include:

- a decline in annual rainfall

- a significant decline in winter and growing season rainfall

- smaller winter rainfalls

- fewer very wet years

- more drier than usual years

- an increase in average maximum and minimum teperatures.

What the records show

There were shifts in climate for Kojonup in the mid-1970s, then again around 2000. Therefore, the analysis is for 1931–1974 (43 years), 1975–2018 (43 years) and 2000–2018 (18 years).

Rainfall

Total annual rainfall has decreased by 8% from 1931–1974 to 1975–2018. The growing season rainfall (April-October) declined by 10% since the mid-1970s with a further 7% decline since 2000 (Figure 1). The chance of 2 consecutive drought years (decile 3 or below growing season rainfall) has increased from 3% in 1931–1974 to 15% in 1975–2018.

Around the mid-1970s there was a shift to consistently drier winter conditions. Figure 2 shows a significant decline in June rainfall from 1931–1974 to 1975–2018.

Figure 3 shows the reduction in June rainfall is due to fewer days with large rainfalls (greater than 5 mm). The average number of rain days each month has remained relatively the same for all months (Figure 4).

Temperature

Since the mid-1970s, mean monthly maximum temperatures have significantly increased in April and May (Figure 5).

Mean minimum temperatures have significantly increased in April and November (Figure 6).

The number of days with extreme temperatures, or maximum temperature above 35˚C, has remained relatively the same (Figure 7).

The number of frost days, or days with minimum temperature below 2˚C, has also remained relatively the same. The average date of the last frost was 3 October in 1931–1974 and 13 October in 1975–2018. Since 2000, the average date of the last frost is 7 October. This indicates that the frost risk around flowering exists (Figure 8).

Projected changes

The following projections for 2035–2064 were obtained using an intermediate emissions scenario (A2) and downscaled data from the CSIRO Global Climate Model CCAM (CMIP3).

Rainfall

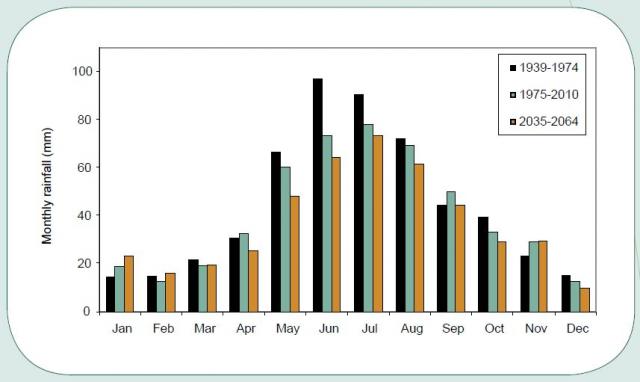

Projections are for less rainfall from April to August (Figure 9).

Temperature

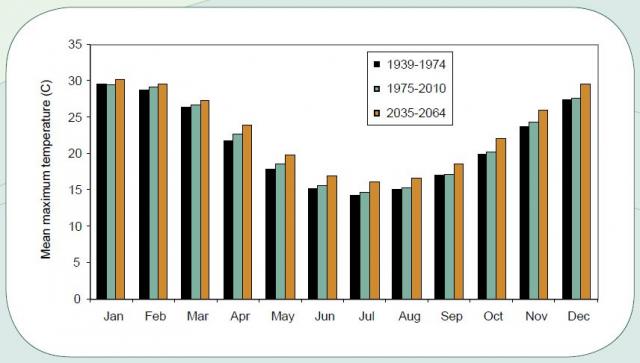

Projections are for increasing mean maximum temperatures (Figure 10).

What are the agronomic implications?

- Since 1975, the start of the growing season has stayed relatively the same (Figure 11). The average start of the growing season, derived from a sowing rule that uses a sowing window starting from 25 April, has remained relatively the same: 20 May for 1931–1974 to 19 May for 1975–2018 and 18 May for 2000–2018.

- The loss of heavy rainfalls in winter has led to a large reduction in reliability of run-off into farm dams. Roaded and natural catchments will need to be 15–20% larger to fill existing dams.

- Declining growing season rainfall and lighter rainfalls mean that evaporation losses are more significant and less water is stored deep in the soil. The greatest risks are increased moisture stress when crops are establishing and finishing.

- Declining winter rainfall will reduce annual pasture production. Flexible lot-feeding or confined feeding systems will need to be established to maintain or finish livestock. Perennial pastures and native pastures should be viewed as a probable alternative to annual pastures.

What are the options for adapting to climate change?

We provide information and technical support for making changes at the incremental, transitional and transformative levels. A general guide is available for each major enterprise and for soil and water resources: