The complex effects of fire

Fire, grazing and weather interacting have complex effects on land condition and animal production for any given type of country.

Recently burned pastures that are regenerating have relatively high productivity, diversity and palatability that is important for many native flora and fauna species. Long-unburnt areas are important for providing breeding and shelter requirements of native fauna and for species with long life cycles, such as mature tree parasites, saprophytes and fungi.

We recommend monitoring rangeland condition, including response to fire, and adapting fire management to the needs of the pasture type, enterprise, lease, manager and season. Fires affect land systems and pasture types in different ways, and have cumulative effects over time.

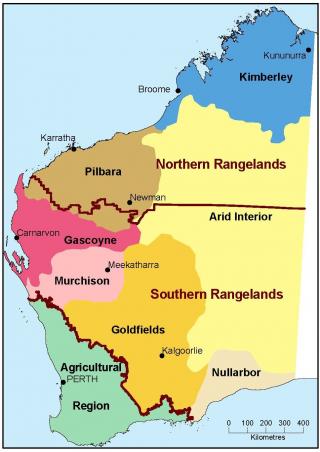

These guidelines for the arid zone (Figure 1) are based on experience and available research findings, providing a starting point for fire management at the property scale.

The arid zone fire risk depends on the season

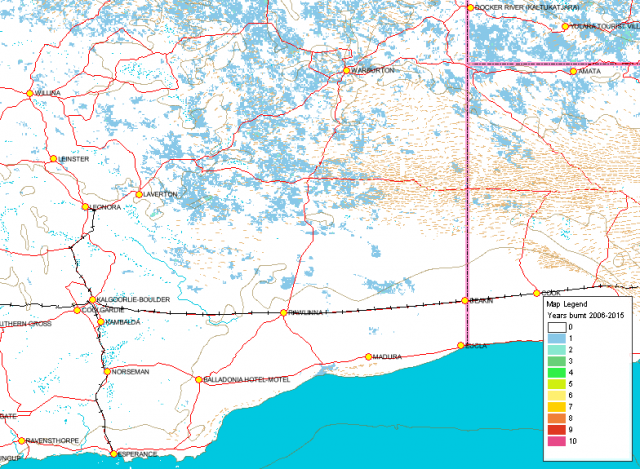

Arid zone pastures in the rangelands occasionally provide enough fuel to carry fires (Figure 2). Seasons with exceptionally high rainfall sometimes occur, causing annual and ephemeral plants to grow and fill in the spaces between perennials, elevating the fire risk in the short term.

Uncontrolled fires pose significant economic, safety, and environmental risks to pastoral enterprises. Controlled burns of arid zone pastures give limited benefit to land management and animal production.

Reduce the risk of damage from fire

You can reduce the risk of damage from fire by following these steps:

- apply these general principles (linked below)

- use visual fuel load guides available from the Department of Fire and Emergency Services (DFES)

- use the guidelines for managing pasture with fire in different types of country (linked below).

Observations in the arid zone are that post-disturbance pasture recovery (including recovery from fire) is strongly correlated with favourable seasonal conditions and good total grazing pressure control.

General principles for managing fire

Uses and timing of planned fires

We recommend that:

- pastoral stations do not use prescribed burning at any time in areas under grazing because of the unreliability of soil moisture available for pasture growth

- pastoral stations with average annual rainfall below 200 millimetres include wildfire mitigation in their property management plan

- pastoral stations in arid zone landscapes under other uses consult the Northern Fire Manager website and other resources for fire advice.

Guidelines for managing pastures with fire in different types of country

Fire-adapted vegetation communities

Nullarbor grasslands

Factors that increase fire risk

Wildfires are a natural feature of the Nullarbor. The landscape is especially susceptible after favourable seasonal conditions have encouraged ephemeral growth. Grasses, such as Austrostipa scabra (speargrass), can produce large fuel loads after winters of above-average rainfall. This growth, when dry, can readily carry fire in the following summer.

Beard (1975) states that "the Nullarbor Plain seems always to have been substantially fire free since a fire would only travel following a good season, when there is a dense growth of tall grass. Occurrence of old fire-tender tree species of Acacia on the plain (A. papyrocarpa, A. aneura) indicates freedom from fire".

Fire frequency on the Nullarbor has increased since European settlement, particularly following the development of the Trans-Australian Railway line and the use of steam trains, and in more recent times with accidental and deliberate roadside fires. Lightning strikes during summer thunderstorms also start fires.

Managing fire risk on the Nullarbor

Better tracks and fencelines have enabled pastoralists to reach and fight fires where they start. Nullarbor pastoralists comment that if they can get to a fire early, while it is still a narrow finger and before a wind change turns the fire into a broad front, they have a chance to extinguish it.

In exceptionally good seasons, pastoralists can amalgamate paddock livestock onto dense swards of speargrass to reduce fuel load and the threat of extensive fires.

Regeneration following fire on the Nullarbor

Hot wildfires kill shrubs. Shrubs provide forage in poor years and they are essential to sustainable pastoralism in the southern arid areas. Shrubs are replaced by faster growing grasses after fire, rendering burnt patches more susceptible to subsequent burning.

Shrub recolonisation of burnt areas eventually occurs, at a very slow rate, and depends on seasonal conditions, total grazing pressure and burning history of the area.

Heath pastures

Fire occurs naturally within heath pastures. Early successional stages support a scattered to moderately close (projected foliage cover of 10–30%) low shrub regrowth from seedlings and fire-adapted resprouters. There is no evidence that increasing the frequency of fires, either by unplanned ignition or prescribed burning, achieves any improvement in pastoral value from the largely inedible regrowth in these pastures. Fires removing stabilising vegetation on dunes will result in erosion.

Arid zone hard spinifex pastures

See Spinifex rangeland pastures and fire

Fire-sensitive vegetation communities

Increased fire frequency has adversely affected the principal vegetation communities of the Goldfields and Nullarbor.

Chenopod shrubland is not adapted to regular fires. At the regional scale, degraded chenopod shrublands lead to an increase in grassy fuels across the landscape: this may form a bridge for fire between more naturally fire-prone plant communities and those that were formerly isolated, and increase the potential for large, landscape-scale fires.

Before European settlement and rabbit plagues, the vegetation was thought to exist as a mosaic pattern in a state of cyclic equilibrium – alternating between chenopod shrublands and grass-dominated patches. The mosaic pattern occurred as a patchwork of burnt and unburnt areas in response to intermittent fires burning non-uniformly.

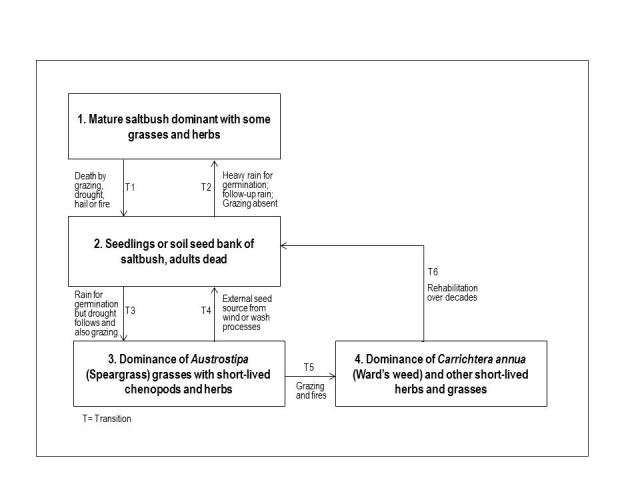

Summer fires occurring after periods of abundant seasonal rainfall can eliminate shrubs. This was observed in the Kalgoorlie–Nullarbor districts following severe fires in 1974–75 when extensive shrub and tree communities were destroyed. The cyclic state of vegetation mosaic in various stages of regeneration became disrupted with the introduction of rabbits, later combined with an increased fire frequency, and in some cases compounded by livestock grazing. The various states and transitions of the Nullarbor Plain chenopod shrubland have been summarised by Gillieson, Wallbrink and Cochrane (1996) (Figure 3).

There has also been extensive alteration to the woodland communities that border the Nullarbor Plain. Encroaching grassland into woodland margins has increased the fire susceptibility of these habitats.

On the Hampton Tableland, areas of myall and mallee woodland on limestone hummocks (low rises) have become surrounded by grassland in the depression corridors. There have been similar changes on the land systems bordering the Nyanga Plain. In some instances fire has completely burnt out the perennial vegetation on the rises. Grazing and subsequent fires have altered the area, tending to favour the expansion of grassland. Fire-sensitive myall has been killed. Grasses growing at the base of myall lead to the trunk being burnt out with the upper branches lying splayed on the ground.

The most common tree on the Nullarbor is the western myall, which is fire sensitive. Widespread natural germination often follows good seasons with above average rain. Large numbers of seedlings will germinate when protected in natural groves, but the survival rate is very low. Young myalls (<20 yrs) are very vulnerable to grazing. Regeneration of western myall is also limited if rabbits are present.

Grazing by livestock and rabbits eliminates seedling germination and the seedbank becomes exhausted. In some instances the only evidence of past woodland is dead branches on the ground. After the next favourable season when grasses are again prolific, fires can consume all woody debris, removing visual evidence that the area once supported any woodland.

In some areas on the Hampton Tableland, fire-tolerant mallees, such as Eucalyptus yalatensis (yalata mallee), have also been eliminated by intense or frequent fires. The evidence of these former wooded habitats comes from charred roots in hollows surrounded by up-ended root-heaved rocks.

Mallee shrubland, sandplain and mixed acacia woodland pastures

We recommend that rangeland managers do not promote fire on these pasture types.

Most of these plant communities are adapted to occasional fire, but the interval between fires is generally long: usually at least 30 years and commonly much longer. Infrequent fire is considered beneficial to pasture productivity. Dry lightning ignition is the most common cause of fire in these communities.

Surface fuel to support large-area fires only occurs after extended periods of above-average rain. Livestock grazing reduces surface fuel, particularly adjacent to water points. Total grazing pressure is a major factor in the incidence of fire on these plant communities.

In mallee shrubland, there is evidence that mallee fowl survival is improved where young mallee regrowth (up to 10 years post-fire) supplies the foraging needs, and areas unburnt for more than 40 years provide breeding and shelter areas. Regional conservation values can be increased by managing the fire interval in some plant communities adapted to low-frequency fire.

Many perennial species, including trees, resprout extensively after fire. Regrowth and early post-fire germination is attractive to livestock and vulnerable to overgrazing. We recommend that livestock are kept off freshly burnt areas until there is effective regrowth. Temporary closure of water points close to newly burnt pastures will help keep livestock and some feral grazers off freshly burnt areas, and native grazers may need to be controlled.

Mulga hardpan pastures

Mulga hardpan pastures should be protected from burning because mulga and many associated shrubs are fire-sensitive. These pastures will not generally carry a fire in average seasons but in good seasons, grasses and herbs supply sufficient fine fuel to carry a fire.

The palatable shrubs of the mulga hardpan pastures of the southern rangelands have been substantially reduced by heavy grazing and subsequent wildfire. The increase of fine grassy fuels as a result of reduced competition by perennial low shrubs has contributed to an increased frequency of fire in these pastures. Palatable perennial grasses are now rare on mulga hardpan intergroves. Unpalatable large shrubs, such as turpentine bush and royal poverty bush, have increased in these pastures because they are not grazed and are less fire-sensitive than the desirable low shrubs.

Chenopod shrublands, samphire and forbland pastures

We recommend that pastoralists actively exclude fire from these pasture types.

Chenopod shrublands, samphire and forbland pastures are less flammable than most other vegetation, and are fire-sensitive. Occasional burning could be used to control shrubs, such as needlebush, though fine fuels may not reach the required loads for the intensity required to kill the woody plants. We recommend fine-scale mosaic burning to allow regeneration from unburnt areas.

These pasture types are extensive in the semi-arid and arid rangelands, typically on saline soils in lower parts of the landscape. The high salt content and relatively succulent character of chenopod shrub leaves renders them less flammable than other vegetation. The risk of fire damage increases with overgrazing which reduces shrub cover and increases the biomass of grasses and forbs, especially after better than average seasons. Grasses and herbs occur as a ground layer and are highly flammable.

Bladder saltbush is a relatively short-lived (~25 years), shallow-rooted shrub. It germinates readily over the cooler months. Seedlings and young plants are very common after good rains. Bladder saltbush cannot withstand any type of fire. Saltbush regeneration is by seed alone, therefore grazing pressure must be reduced post-fire to minimise the risk of exhausting the seed bank. Valuable bladder saltbush has been completely eliminated in some areas.

The ability of pearl bluebush to regenerate after fire, and cope with arid conditions, has allowed it to become a dominant climax species. Pearl bluebush has deep roots, grows slowly and is long-lived (>200 yrs). Pearl bluebush will tolerate a ‘cool’ fire, but recovery is slow; it can be killed by a hot fire. Regeneration is difficult and usually requires a number of consecutive favourable seasons for re-establishment to occur.

Fire temperature affects the degree of damage:

- A cool, moderate burn may not kill Maireana sedifolia (pearl bluebush), though its recovery from fire is slow.

- Any type of fire will kill Atriplex vesicaria (bladder saltbush).

- Bluebushes are fire-sensitive and the community will suffer from a loss of stored seed and desirable shrubs following a fire.

Post-fire regeneration of chenopod shrubs is only by seed. Grazing pressure must be reduced to allow post-fire recovery and preserve the seedbank.

Fires in these vegetation types will reduce foliar cover and increase the risk of soil erosion.

Grazing management is important for preventing fire

Retaining the dominant chenopod shrub biomass is the most appropriate way of preventing fires. If shrub degradation starts, reduce total grazing pressure. Major components of both the short-lived herbage and the chenopod shrub foliage are palatable to livestock, particularly when good quality (low salinity) stock water is provided.

References

- Beard, JS 1975, 'Vegetation survey of Western Australia: Nullarbor: Explanatory notes to sheet 4', 1:1 000 000 Vegetation Series, University of Western Australia Press, Perth.

- Chilcott, CR, Rodney, JP, Kennedy, AJ & Bastin, GN 2005, Grazing land management – central Australia version, workshop notes, EDGEnetwork Future Beef Program, Meat and Livestock Australia.

- Cowley, R, Pettit, C, Cowley, T, Pahl, L & Hearnden, M 2012, 'Optimising fire management in grazed tropical savannas', in Proceedings of the 17th Australian Rangeland Society Biennial Conference, Australian Rangeland Society: Australia.

- Gillieson, DS, Wallbrink, P & Cochrane, JA 1996, ‘Vegetation change, erosion risk and land management on the Nullarbor Plain, Australia’, Environmental Geology, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 145–153.

- Payne, AL, Spencer, GF & Curry, PJ 1987, 'An inventory and condition survey of rangelands in the Carnarvon Basin, Western Australia', Technical bulletin 73, Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia, Perth, researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/tech_bull/2/

- Ryan, K, Novelly, P, & Dray, R 2013, Grazing land management – Pilbara version, workshop notes, EDGEnetwork, Future Beef Program, Meat and Livestock Australia.

- Stretch, J 1996, ‘Fire management of spinifex pastures in the coastal and west Pilbara',Miscellaneous publication 23/96, Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Perth.

- Stretch, A & Addison, J (eds.) 2005, 'Fire management guidelines for southern shrubland and Pilbara pastoral rangelands', Best management practice guidelines series, Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Perth.

- van Vreeswyk, AM, Leighton, KA, Payne, AL & Hennig, P 2004, 'An inventory and condition survey of the Pilbara region, Western Australia', Technical bulletin 92, Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia, Perth, researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/tech_bull/7/

- Waddell, PA, Gardner, AK & Hennig, P 2010, 'An inventory and condition survey of the Western Australian part of the Nullarbor region', Technical bulletin 97, Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia, Perth, researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/tech_bull/10/

- Walsh, D, Crowder, S, Saggers, B & Shearer, S 2012, ‘Early wet season burning and pasture spelling to improve land condition in the Victoria River District, NT’, in Proceedings of the 17th Australian Rangeland Society Biennial Conference, Australian Rangeland Society, Australia.