Agronomy options to enhance the impacts of weed management

Some agronomic practices can improve crop environment and growth, along with the crop's ability to compete with weeds. These include crop choice and sequence, improving crop competition and improving pasture competition.

Crop choice and sequence

The ability to compete with weeds varies between crop type and variety. In paddocks with lots of weeds, a competitive crop can reduce weed seed-set and reduce the impact the weed has on crop yield.

Generally cereal crops are more competitive with oats ranked the highest, then barley then wheat.

Plan crop rotations in advance to minimise disease and insect problems and maximise crop fertility. If these are managed optimally, crops then become more competitive against weeds. Some weed management tactics rely on specific crop type and variety, or the sequence of cropping.

Improving crop competition

The impact of weeds on crop yield can be reduced and the effectiveness of weed control tactics increased by improving crop competition. The rate and extent of crop canopy development are key factors influencing a crop’s competitive ability with weeds. A crop that rapidly establishes a vigorous canopy, intercepting maximum sunlight and shading the ground and inter-row area, will provide optimum levels of competition.

Canopy development can be influenced by:

- Crop and variety: Oats are the most competitive against annual ryegrass, whilst chickpeas and lupins have shown limited ability to compete against weeds.

- Row spacing, sowing rate and sowing depth: Increasing sowing rate can result in earlier crop canopy closure and greater dry matter production, resulting in improved weed suppression. Narrow crop rows usually deliver much better crop competition than wider rows. Maximum competitive ability will come from a crop sown at optimum and uniform depth to get rapid and uniform establishment.

- Crop row orientation: The competitive ability of cereal crops can be increased by orientating crop rows at a right angle to the sun light direction, that is, sow crops in an east-west direction. East-west orientation more effectively shade weeds in the inter-row space than north-south crops. The shaded weeds have reduced biomass production and reduced seed set. In particularly weedy fields, the reduced weed growth leads to increased crop yield.

- Crop nutrition and disease: A healthy crop will best compete with weeds

- Environmental conditions including soil properties and rainfall: Matching the crop (and variety) to the soil type can improve crop vigour and biomass production, which in turn will optimise crop competitive ability. Time of sowing also has a direct impact on the competitive ability of a crop. Delaying sowing beyond the optimum window recommended in a given district will reduce early vigour, extend the time taken to reach canopy closure and reduce overall dry matter production.

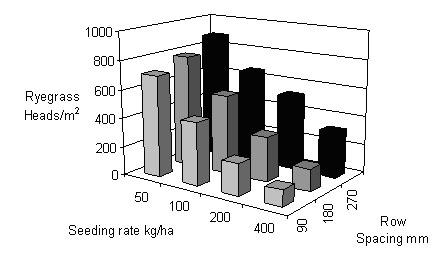

This figure shows the seed rate and row spacing effects of wheat (cv. Arrino) on weed growth. High seed rates and narrow row spacing has significantly suppressed ryegrass growth. [Minkey, Reithmuller and Hashem (1999)]

Improving pasture competition

Pastures represent an important component of many rotations, and normally take 1–5 years to break up extended periods of cropping. Incorporating pastures can help restore soil fertility (organic matter and soil nitrogen) that may have declined due to frequent cropping, and in turn improve the competitive ability of crops.

Pastures provide a valuable opportunity to manage weed problems using tactics not able to be used in cropping situations, such as grazing, mechanical manipulation and non-selective herbicides. Change the timing of these tactics to fit into vulnerable stages of the weed life cycle, for example:

- Time the grazing pressure to manipulate pasture composition. For more information refer to Pasture manipulation for grass control.

- Spray-graze, where grazing is used in conjunction with herbicides. This is a technique for the control of broad-leaved weeds (often capeweed) in pasture and relies on the winter application of sub-lethal rate of herbicides (usually MCPA) to induce plants to wilt. This increases their palatability and animals (at a high stocking rate, seven days after spraying) graze them in preference to clovers and grasses which are not affected by the herbicide. It is important that the treated pasture has a good legume base to compete with the weeds and provide stock feed when the weeds are killed and that they are grazed heavily after spraying so the weeds do not recover. Spray-grazing needs to be repeated each year until the dormant weed seed is exhausted. Note that spray-grazing cannot be used in a medic pasture. For more information refer to Spray grazing - for broadleaf weed control in pastures.

- Exploit the differences in species acceptability to sheep, for example, grasses are more palatable in autumn