Description and life history

Adult moth

The adult form of the native budworm is a moth that has rapid, low-level flight that takes a zig-zag path and ends with a dive into a crop or shrubs.

The moths have light brown, patterned forewings and mostly pale hind wings with a black patch at the tail end.

Eggs

White spherical eggs (0.5mm) are laid singly, mostly near the top of the plant. The eggs darken as they mature and tiny caterpillars hatch after about seven days.

Caterpillars

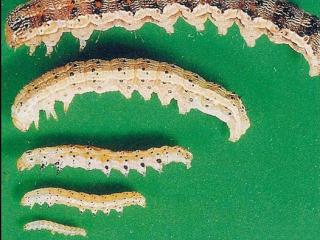

The young caterpillars feed on leaf or pod material for about two weeks before they become large enough (5mm long) to be noticed in the crop.

It takes a further four weeks until they are fully grown (40mm long) which is about seven weeks from the time of egg laying.

These development times are based on average spring temperatures when caterpillars are active in central cropping areas of Western Australia. Later in the season, or in more northerly areas, developmental rates for caterpillars will be faster.

The caterpillars vary greatly in colour from green through orange to dark brown and are often seen with their heads inside pods. They usually have dark stripes along the body and are sparsely covered with fine bristles.

New moth flights and egg laying will result in caterpillars of varying sizes in a crop. Caterpillars eat increasing quantities of seed and plant material as they grow with the last two growths stages (fifth and sixth instar) responsible for eating over 90% of their total grain consumption.

Pupa

When fully mature, the caterpillars crawl to the ground, burrow into the soil and pupate. The length of the pupal stage depends on several environmental factors and varies from two weeks to several months.

Mortality of eggs and caterpillars

Only a small proportion of eggs laid by moths survive to the damaging large caterpillar stage. There is a high death rate in the egg and small caterpillar stages. Eggs may be dislodged and small caterpillars may become stuck or drown due to wet weather.

Predators and parasitoids also affect population numbers and can suppress them below economic damage thresholds.

If numbers of native budworm are high, populations can crash due to viruses and disease.

Plant hosts

Native budworm caterpillars most frequently attack the fruiting parts of plants but also feed on the terminal growth, flowers and leaves.

All pulse and canola crops grown in Western Australia are susceptible to attack, especially when pods are present. This includes field pea, faba bean, lentil, chickpea, lupin and canola.

Serradella, lucerne, clover and annual medic seed crops may be attacked, as well as a large range of horticultural crops.

Cost of native budworm

Losses attributed to native budworm come from direct weight loss through seeds being wholly or partly eaten.

Grain quality may also be downgraded through unacceptable levels of chewed grain or fungal infections introduced via caterpillar entry into pods, especially in faba bean and albus lupin pods.

The percentage of broken, chewed and defective seed found in grain samples affects the final price of pulse crops marketed for human consumption. This applies particularly to the large-seeded crops such as faba bean, kabuli chickpea and field pea.

Monitoring for adult moths

Male moths are easily captured in pheromone (female sex scent) traps. These traps are maintained by Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development staff and volunteer farmers and provide an early warning of moth arrival and abundance.

Results from native budworm traps together with other pest and disease alerts are published weekly throughout the growing season in PestFax. The PestFax newsletter is distributed via email and requests for free subscription can be sent to pestfax@dpird.wa.gov.au.

Crop susceptibility and risk periods

Crops vary in their attractiveness to moths as sites for egg-laying. Moths generally prefer crops in the following order:

- lentil

- field pea

- faba bean

- chickpea

- lupin

- canola.

Crop density and crop growth stage (flowering and podding) will affect the number of eggs laid by the native budworm moths.

The feeding behaviour of caterpillars also changes according to the type of crop the caterpillars are feeding upon.

Field pea, chickpea, lentil and faba bean crops

- Are very susceptible to all sizes of caterpillars during the formation and development of pods.

- Tiny caterpillars can enter emerging pods and damage developing seed or devour the entire contents of the pod.

- Some field pea growers have had unexpected losses from native budworm damage in semi-leafless field peas like Kaspa as these are more difficult to sample with their intertwined tendrils.

Lupin crops

- Narrow-leafed lupin crops will not be damaged until they are close to maturity and the pods are losing their green colouration.

- Pod walls are not penetrated until the caterpillars are over 15mm in length.

Canola crops

- Canola is similar to narrow-leafed lupin, pods only become attractive to caterpillars as the crop nears maturity and begins to hay-off.

- Caterpillars of all sizes will enter pods at this stage, with larger caterpillars doing the most damage.

- Native budworm can also cause damage after a canola crop has been swathed. This will occur if the crop is swathed when many pods are still green with soft seed or if swath drying is prolonged due to cool damp conditions.

Monitoring

Sampling of crops to determine the abundance of caterpillars is essential. The quickest and easiest method to sample most crops is to sweep with an insect net, taking 2m long sweeping arcs, using the standard net size (380mm diameter).

Multiples of 10 sweeps should be taken in several parts of the crop. If more than 10 consecutive sweeps are made, there are likely to be too many dead flowers and leaves in the sample to locate the small caterpillars easily.

Netting is most efficient in short and thin crops and less efficient in tall dense crops. It is very important to keep the lower leading edge of the sweepnet slightly forward of the net opening so that dislodged grubs are picked up and carried into the net.

Field pea crops

To monitor for native budworm caterpillars in:

- semi-leafless field pea crops, use grub counts based on 20 sweeps of a sweep net

- for trailing type field pea crops use 10 sweeps of a sweep net.

Semi-leafless peas are more difficult to sample with their intertwined tendrils. The sweeping efficiency in semi-leafless peas is about half the efficiency of that in conventional trailing types like Helena.

Lupin crops

Narrow-leafed lupin crops will not be damaged until they are close to maturity and the pods are losing their green colouration. At this stage it will be difficult to use a sweep net as the plants are stiff and the pods are spiky.

An alternative to sweeping is:

- to cut plants from several places in the crop

- at each smaple point shake plants into a bin to count caterpillar numbers.

Take small areas from the crop, either a tenth of a square metre, or a number of plants equal to that found in a square metre. This is the easiest method for assessing damage levels for the entire crop.

Control

When to spray

The decision to spray for:

- field pea, chickpea, lentil and faba bean crops needs to be considered from the time of first podding

- lupin and canola can be left until pods are beginning to mature.

If caterpillar numbers are below the threshold levels provided (see section on theresholds), the decision to spray should be delayed and periodic sampling continued. One well-timed spray to control native budworm caterpillars should be sufficient in most situations.

Sweep netting of the crop should be carried out after spraying to confirm that the required level of control has been obtained. Effectively applied synthetic pyrethroids will prevent reinfestation for up to six weeks after spraying. Subsequent caterpillar hatchings will usually be too late to cause any damage.

Economics of spraying

The number of caterpillars present in a crop is the major factor determining whether economic damage will occur. Results from many trials conducted by DPIRD have been used to generate the table below to give a personalised and more precise measure of potential loss from native budworm damage.

Crop loss (kilograms per hectare) for each caterpillar netted in 10 sweeps (or found per square metre) is shown in the table. For one caterpillar netted in 10 sweeps is equivalent to about 20 000 caterpillars per hectare for most pulse crops.

How to use the threshold table

The losses given (Table 2) are for the number of caterpillars netted in crops during early pod formation for all crops except lupins and canola. For these canola and lupins numbers are during pod maturation.

To use the table you need to substitute:

- control costs with your own actual costs

- expected grain price per hectare based.

This will calculate the economic threshold or the number of caterpillars that will cause more financial loss than the cost of spraying.

| The on-farm value of field peas is $300 per tonne (t) The cost of control is $12 per hectare (ha) ET = C ÷ (K x P) Where: ET = Economic threshold (numbers of grubs in 10 sweeps) C = Control cost ( includes price of chemical + application) ($ per ha) K = Kilogram per hectare (ha) eaten for every one caterpillar netted in 10 sweeps or per square metre (see Table 2) P = Price of grain per kg (price per tonne ÷ 1000) Therefore economic threshold for field pea = 12 ÷ (50 x (300 ÷ 1000)) = 0.8 ~ 1 grub per 10 sweeps |

| Crop | P Grain price per tonne | C Control costs including chemical + application | K Loss for each grub in 10 sweeps (kg/ha/grub) | ET Grubs in 10 sweeps | ET Grubs in 5 lots of 10 sweeps | ET Grubs (>15mm) per m2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field pea - trailing type (for example, Helena, Dundale) | e.g. 300 | 10 | 50 | 1.0 | 5 | - |

| Field pea - semi leaf less (for example, Kaspa) | e.g. 300 | 10 | 100 | ~1 | 3 | - |

| Chickpea | e.g. 420 | 10 | 30 | ~1 | 4 | - |

| Faba bean | e.g. 280 | 10 | 90 | ~1 | 2 | - |

| Lentil | e.g. 520 | 10 | 60 | ~1 | 1.5 | - |

| Canola | e.g. 500 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 15 | - |

| Lupin | e.g. 370 | 10 | 7 | ~4 | 19 | 5.1 |

Note: Growers using this table to calculate spray thresholds should substitute their own control costs and the current on-farm grain price expected.

Where:

ET = Economic threshold (numbers of grubs in 10 sweeps)

C = Control cost ( includes price of chemical + application) ($ per ha)

K = Kilogram per hectare (ha) eaten for every one caterpillar netted in 10 sweeps or per square metre

P = Price of grain per kg (price per tonne ÷ 1000)

Adjusting thresholds

Use of the table and calculations will provide a personalised and more precise measure of potential loss from native budworm damage. Sometimes the loss would turn out to be less than predicted, if, for example, the season is shortened by a lack of moisture.

Premiums paid for exceeding quality standards for high value and large-seeded pulses (like Kabuli chickpea) may necessitate even lower thresholds than those provided in the table.

Acknowledgements

Native budworm research was supported by the Grain Research and Development Corporation.

Valuable contibutions were provided by Phil Michael, Phil Lawrence and Darryl Hardie.