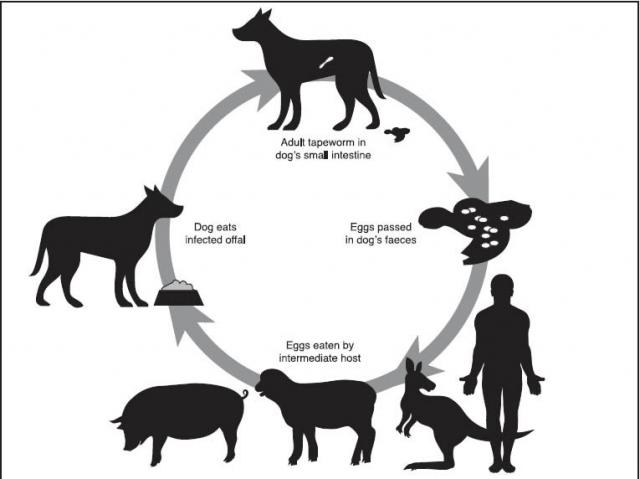

The adult stage of the parasite is found in the intestines of dogs while the intermediate or larval stage (the cysticercus) is found in the muscles of sheep. The intermediate stage in sheep is characterised by small cysts in the muscle tissue. When these cysts are eaten by a dog, the adult parasite develops in the dog’s intestine and the lifecycle continues (foxes can also carry T.ovis but are a poor host and are considered of minor significance in transmitting the infection).

Over time the cysts in the muscle degenerate and are no longer infective. They calcify and form a small nodule with a ‘gritty’ texture. This is the stage that is commonly known as sheep measles.

T. ovis does not present a public health risk, however these calcified cysts are unpleasant to eat and can result in carcasses being downgraded or even condemned at the abattoir. T. ovis infection also has the potential to impact on valuable export markets for Australian lamb and mutton.

Control of T. ovis

Control can be difficult on a single-farm basis. The basic rules for control include:

- Every four weeks, worm all dogs on the property with a wormer containing the active ingredient ‘praziquantel’.

- Prior to feeding, properly cook or freeze any sheepmeat fed to farm dogs. Cooking and freezing inactivates the cysts.

- Lock dogs up when not working and at night to reduce the risk of scavenging of sheep carcasses.

- Dispose of dead sheep on farm by burning or burial so that they cannot be scavenged.

- Do not allow contractors’ dogs or other dogs into sheep paddocks or yards unless they have been treated with a praziquantel wormer within the last four weeks. Sheep on a property where control of T. ovis is good have no immunity to the parasite. The arrival of untreated dogs on such farms has been associated with very high rates of T. ovis infection in the sheep.

The intermediate or larval stage of T. ovis has been shown to be carried some distance by flies so control should be seen as a district issue. It is a good idea to coordinate your dog worming program with your neighbours and ensure dogs do not roam between properties.

Recent research has shown that the adult T. ovis is carried by foxes as well as dogs. The basics of control remain centred on the farm dog, but if you are seeing continuing problems with sheep measles despite proper management of farm dogs, spread from foxes should be considered. Control from this source should include:

- regular planned programs of baiting or shooting of foxes

- prompt disposal of carcasses by burning or burying so that foxes cannot scavenge them

- avoiding using paddocks next to known fox habitats for lambing ewes and weaners.

Once a sheep is infected with T. ovis the cysts are present for life. Therefore once you start a control program in your dogs, you may continue to see sheep measles in sheep sent to abattoir for a while. With time and persistence however, control can be achieved.

The lifecycle of T. ovis is basically the same as that for Echinococcus (hydatid tapeworm). This parasite does have human health implications. Any program that controls sheep measles will also control hydatid tapeworm.

For more advice on control of T. ovis, contact your local department veterinary officer. Refer to Livestock biosecurity program contacts for more information.