Rangeland regions of Western Australia

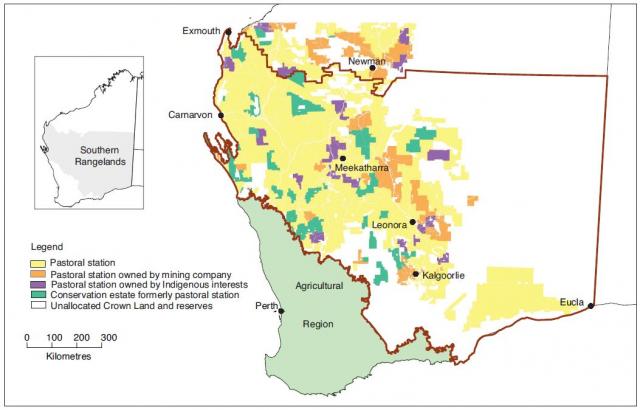

The rangelands cover about 2.2 million square kilometres (87% of WA, which is all but the south-west agricultural region), and pastoral stations for grazing livestock cover 857,833 square kilometres (km2) of that, based on active leases as at June 2016. The rest of the rangelands consist of land vested for conservation, Indigenous purposes and unallocated Crown land. A map of all Western Australian pastoral land tenure is available in the DPIRD Digital Library.

The rangelands are highly varied and are contained wholly or partly within 20 IBRA (Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia) bioregions. These rangelands have climates ranging from tropical to arid temperate; with topography including coastal plains, rocky ranges and semi-arid desert; and rainfall amount and distribution ranging from summer-dominant with 1200 mm annually to winter-dominant and less than 250 mm. The combination of climate, topography and soils renders them unsuitable for broadacre farming, and so land use is typically limited to pastoralism.

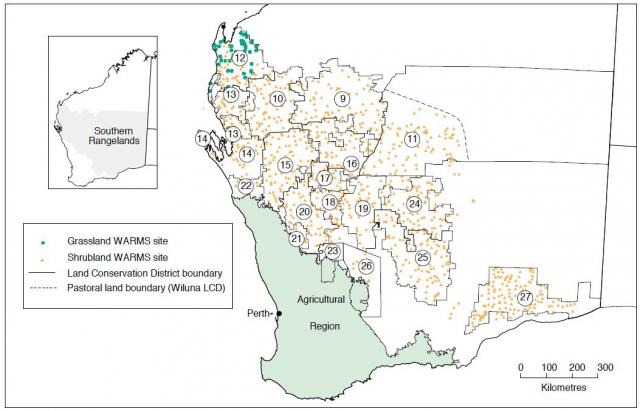

The Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD) recognises 2 main rangeland types, based on dominant vegetation type (Figure 1):

- The northern rangelands, which contains the Kimberley (206,775 km2) and the Pilbara (147,940 km2) regions. This is characterised by grasslands.

- The southern rangelands, which is mostly south of the Pilbara region and between the south-west agricultural region and the arid interior. It contains the Gascoyne (138,650 km2), Murchison (128,620 km2) and the Goldfields–Nullarbor (235,850 km2) regions. This is characterised by shrublands.

Pastoral management

DPIRD has developed a contemporary risk-based management framework based on internationally accepted best practice principles, to achieve the Western Australian Government’s objective to improve pastoral land condition and economic opportunities, and to meet the Office of the Auditor General's recommendations of meeting the principles of Ecologically Sustainable Development (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 - Section 3A),

The Framework for Sustainable Pastoral Lands Management – Revised edition (Framework) is consistent with the State Natural Resource Management Program (NRM Framework 2018) and with the risk-based approaches endorsed internationally by the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) for application to their NRM programs. DPIRD is developing pastoral soil and pasture condition standards to provide management and compliance clarity on acceptable and unacceptable pastoral land condition. The Framework and standards will be revised as new technology and new data becomes available from pastoral monitoring and assessment.

DPIRD has also produced the Framework for sustainable pastoral management - Land condition version, a shorter and more targeted description of the monitoring, assessment and compliance processes for pastoral land condition (soils and pastures).

The goal of pastoralism is a profitable livestock business, while maintaining the land and vegetation in good condition. Pastoral management is a balancing act – to maintain pastures and soil in good condition while balancing grazing pressure and fire management in response to highly variable seasonal conditions.

Land tenure in the rangelands is predominantly pastoral leasehold under the Land Administration Act 1997. This Act requires pastoral lessees to manage the lease on an ecologically sustainable basis. In addition, under the Soil and Land Conservation Act 1945, the Commissioner of Soil and Land Conservation (the Commissioner) has the duty and powers to prevent activities that could lead to land degradation and, if warranted, the power to instruct lessees to ameliorate or repair degraded land.

Rangeland vegetation

The rangeland vegetation types range from grasslands to shrublands to woodlands, and include small patches of monsoonal forests in the north. The 2 distinct types of rangelands used for grazing livestock are:

- Grasslands, which are predominantly perennial tussock (bunch) and hummock grasses, with or without some tree cover. They occur mainly in the northern rangelands.

- Shrublands, which are vegetation types characterised by shrubs with a variable acacia or eucalypt overstorey. They occur mainly in the southern rangelands.

Grasslands and shrublands are present in the southern Pilbara and Gascoyne (Figure 1).

Perennial vegetation in the southern rangelands is adapted to characteristically low and highly variable rainfall, and pasture productivity is low relative to that in the northern rangelands. Because of these conditions, management of grazing pressure in the southern rangelands is particularly difficult, and has resulted in extensive areas of poor rangeland condition.

The pastoral industries

Northern rangelands

The pastoral industries in the Kimberley and Pilbara are similar; having a high proportion of tropically adapted breeding cattle. Pastoralists in the Kimberley sell most cattle for live export, and pastoralists in the Pilbara sell for live export and domestic markets. See The Western Australian beef industry web page for more information.

Southern rangelands

The Gascoyne, Murchison, Goldfields and Nullarbor were major wool-producing areas as recently as the early 1990s. However, the number of sheep, especially Merino sheep, has greatly declined since then. Merinos have been replaced to some extent by meat sheep on stations in the western Gascoyne and Murchison, but the most significant change has been a move from sheep to cattle across the southern rangelands. Rangeland sheep production now comprises less than 3% of the total value of the WA sheep production.

The southern rangelands goat population was estimated in 2016 to be between 150,000 and 250,000, although goats are less common in the Goldfields and eastern Murchison. Pastoralists in some southern rangelands areas reported in 2017 that there was an increase in the goat population.

There has been a de facto managed goat industry and an industry based on the sale of unmanaged (feral) goats. Opportunistic harvesting of goats has provided significant and timely income for many leaseholders, with some leaseholders partly managing feral goat flocks rather than simply harvesting.

We recommend that you read Reading the rangeland: a guide to the arid shrublands of Western Australia for a broad coverage of the region. The principles in this document are still sound, even though published in 1995.

Climate

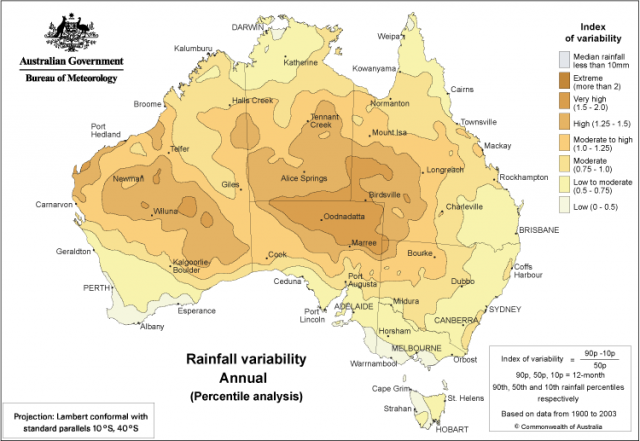

Climate, particularly the amount, intensity and seasonal distribution of rainfall, is a major determinant of rangeland productivity. Dealing with rainfall variability is a major component of rangeland management (Figure 2).

Northern rangelands

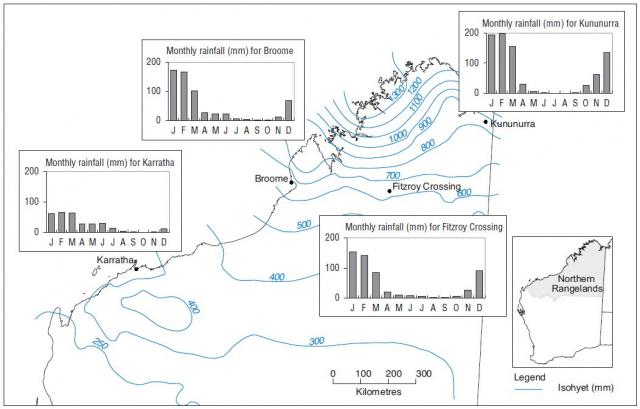

The Kimberley has a tropical climate with 2 dominant seasons separated by short transitional periods:

- The wet summer season (November to April) is hot and humid, with seasonal rainfall up to 1200 mm in the north (Figure 3). Typically, 90% of annual rainfall occurs during this period, when low pressure systems and unstable air dominate.

- The dry winter season (May to October) is influenced by high pressure systems and a predominantly south-easterly airflow from the interior. This rainfall pattern leads to tropical savanna vegetation in the north and arid desert grassland in southern parts.

Although more productive than the southern rangelands, seasonal variability in the northern rangelands means that matching forage demand (stocking rate) with supply (available forage) over a run of seasons is difficult.

The Pilbara has a similar summer and winter seasonal pattern to the Kimberley, with generally lower annual rainfall (300–500 mm) and more frequent poor wet seasons. The southern Pilbara occurs roughly on the boundary between the summer-dominant and winter-dominant/seasonally uniform rainfall zones.

Southern rangelands

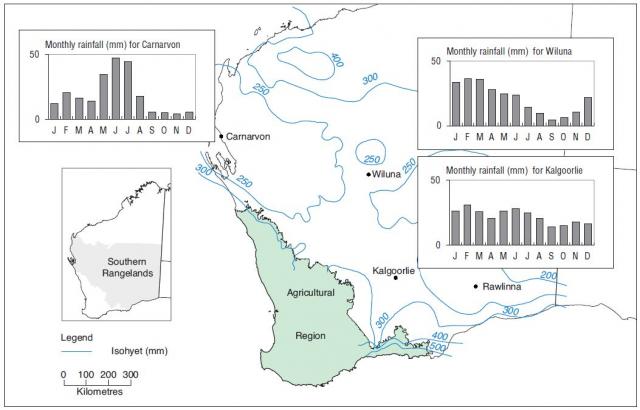

The southern rangelands have predominantly winter rainfall, with an average annual rainfall generally below 300 mm (Figure 4). Rainfall is highly variable within and between years, and variation is high compared to similar areas elsewhere in Australia.

This arid climate, with frequent dry years interspersed with occasional high rainfall events, makes it particularly difficult to match forage demand (stocking rate) with supply (available forage). Summer rainfall is usually low throughout the region, although the proportion of annual rainfall occurring in the summer months has increased over recent decades. Substantial variation in rainfall also occurs in cycles that vary from 2.5 to 30 years or more.

Climate change and the WA rangelands

High seasonal variability in the rangelands masks climate change to some extent.

Climate records indicate a drying trend for much of WA, except for the Kimberley, and modelling suggests a continued warming trend over the coming decades (see Climate change and the pastoral industry).

Northern rangelands

Rainfall in northern Australia, including the Kimberley, is likely to be heavier, with more rain falling per rain day. As a result, flash floods may become more common. There are likely to be more dry days (time between rains), which may cause water supply problems.

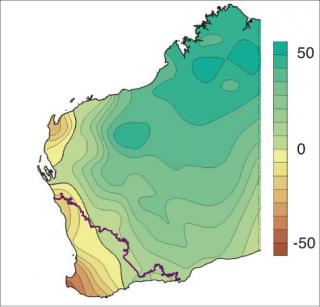

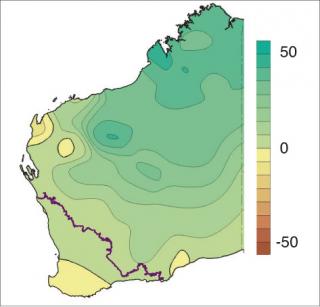

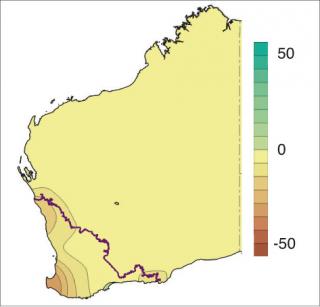

In north-western Australia, the wet season is becoming wetter and, since the 1950s, annual rainfall has increased by more than 30mm per decade and exceeding 50 mm per decade over parts of the north-west coast (Figure 5). This increase in annual rainfall has generally been associated with an increase in summer rainfall (Figure 6) and a slight decrease in winter rainfall (Figure 7).

Southern rangelands

In the decade 2005–14, all LCDs in the southern rangelands had more years with above-average summer rainfall (6 to 9 years out of 10) than the long-term above-average rainfall in a 10-year period (3 to 4 years out of 10).

In the period 2005–14, there were significant changes in the average monthly rainfall compared to the long-term monthly rainfall (Table 1).

| Month | Change in rainfall | Amount of change (mm) | Percentage change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| December | Increase | 9 | 76 |

| January | Increase | 18 | 82 |

| March | Increase | 13 | 50 |

| May | Decrease | –10 | –32 |

| June | Decrease | –12 | –36 |

Legislation, land tenure and pastoral leases

Land tenure in the rangelands is predominantly pastoral leasehold, with leases issued under the Land Administration Act 1997. The statutory authority for managing the pastoral estate rests with the Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage and the Pastoral Lands Board of Western Australia (PLB). DPIRD provides technical assistance to the PLB to support their activities.

The Land Administration Act states that the function of the PLB is to ensure that pastoral leases are managed on an ecologically sustainable basis. Leases are developed and assigned to enable them to be worked as an economically viable and ecologically sustainable pastoral business unit.

In addition, under the Soil and Land Conservation Act 1945, the Commissioner of Soil and Land Conservation (the Commissioner) has the duty and powers to prevent activities that could lead to land degradation and, if warranted, the power to instruct lessees to ameliorate or repair degraded land.

A pastoral lease is a title issued by the Minister for Lands for the lease of an area of Crown land for the limited purpose of grazing of livestock (cattle, sheep, goats and horses) and ancillary activities. Under the Land Administration Act and the Soil and Land Conservation Act, pastoral lessees are obliged to manage the vegetation and soil resources on their lease to avoid soil and land degradation and, under the Biosecurity and Agricultural Management Act 2007, to control declared plant and animal pests.

A permit from the PLB is required for any non-pastoral use carried out on a pastoral lease. A permit may be granted if the property as a whole continues to be managed for pastoral purposes. Mining leases may be issued concurrent to pastoral leases and mining operations can occur on pastoral land.

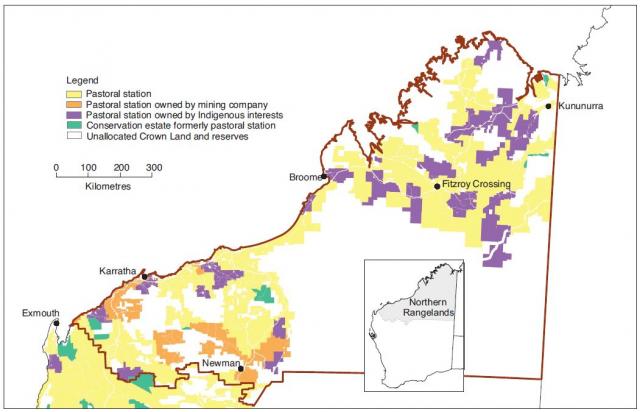

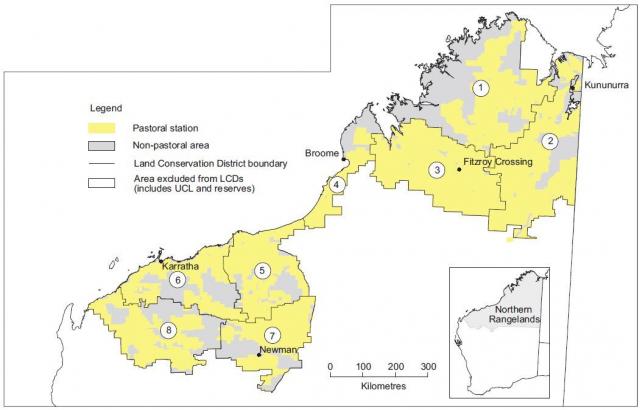

In 2016, there were 491 registered pastoral leases in WA, held in 436 pastoral stations: 152 stations in the northern rangelands (92 in the Kimberley and 60 in the Pilbara); and 284 stations in the southern rangelands. Lease ownership includes large corporations, private companies, family operations, Indigenous organisations, and, particularly in the Pilbara and Goldfields, mining companies (Figures 8 and 9).

Pastoral land tenure maps

Detailed GIS maps can be downloaded from the links below. The links will switch you to a new page.

- Western Australia Pastoral Land Tenure – State

- Western Australia Pastoral Land Tenure – Kimberley Region

- Western Australia Pastoral Land Tenure – Pilbara Region

- Western Australia Pastoral Land Tenure – Gascoyne Region

- Western Australia Pastoral Land Tenure – Murchison Region

- Western Australia Pastoral Land Tenure – Goldfields–Nullarbor Region

Land conservation districts

Reporting for legislative purposes is at LCD scale. Pastoral LCDs, as with all LCDs, are appointed under legislation, constituted under section 22(1) of the Soil and Land Conservation Act 1945 and comprise pastoral leasehold land, defined conservation areas (which may have formed part of the pastoral estate prior to their declaration as conservation areas) and unallocated Crown land.

Land conservation district committees (LCDCs) are community-based groups focused on sustainable resource management and their role is to promote on-ground involvement in voluntary land management and conservation activities. Many LCDCs also manage externally-funded projects aimed at preventing land degradation and promoting soil and land conservation and reclamation. In WA, the Commissioner resides within DPIRD and provides administrative services for the LCDCs, including a state officer (a nominee of the Commissioner), insurance, information and administrative funds. Note that not all LCDs have active committees.

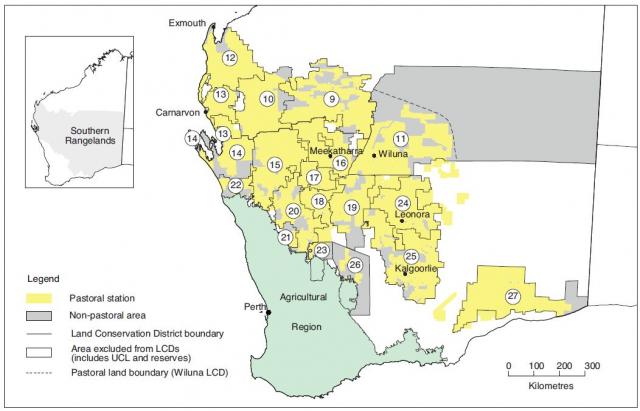

There are 27 LCDs in the WA rangelands (Figures 10 and 11).

Northern rangelands

There are 8 LCDs in the northern rangelands: the Kimberley LCDs are Broome, Derby – West Kimberley, Halls Creek – East Kimberley and North Kimberley; the Pilbara LCDs are Ashburton, De Grey, East Pilbara and Roebourne – Port Hedland.

Southern rangelands

The southern rangelands has 19 LCDs which have been subdivided based on rainfall distribution. The Gascoyne – Ashburton Headwaters, Upper Gascoyne and Wiluna LCDs are classed as ‘southern rangelands (SR) summer’ because they receive a substantial proportion of their annual rainfall in summer. The rest of the LCDs are classed as ‘SR winter’.

Rangeland resources and change

The goal of sustainable pastoralism is the continued use of rangeland natural resources for livestock production without causing a loss of land capability. To monitor achievement of this goal, we need to know the starting condition (baseline), changes over time of the natural resources used in pastoralism, and the sustainable carrying capacity for livestock.

Rangeland surveys

Rangeland surveys provide the baseline data for pastoral resource condition and estimates of pastoral value. This baseline data is used to determine rangeland vegetation in ‘good condition’ for different land systems. Rangeland surveys provide information about the amount of vegetation available for grazing on these good condition land systems, and this is used to estimate the potential carrying capacity (PCC) for the land systems, LCDs and rangeland regions. See the rangelands glossary for an explanations of PCC.

Fourteen condition and inventory surveys have been completed and surveys now cover about 87% of the state’s pastoral rangeland. Beard’s vegetation mapping (Beard 1975) is used to provide information for those areas not surveyed (the southern Goldfields and areas east of Wiluna).

Carrying capacity as a measure of sustainable pastoral productivity

Pastoral business viability relies on being able to turn-off a sufficient number of livestock to meet market requirements. DPIRD estimates the current carrying capacity (CCC) of stations from vegetation condition (good, fair, poor for each pasture type within a land system) and pastoral values (livestock units per unit area) of the pastures that make up the station.

Regular on-station assessments used to calculate CCC finished in 2009 or earlier. Since 2009, range condition assessments (RCAs) of stations have been based on the degree of risk of falling land condition. DPIRD has moderate to high confidence in the overall CCC estimates based on pre-2009 RCAs, risk analysis RCAs, analysis of WARMS (Western Australian Rangeland Monitoring System) data, seasonal quality, and remote sensing data (Normalised Difference Vegetation Index and cover).

The fall from PCC to current carrying capacity (CCC) gives an indication of the degree of degradation in resource capability for pastoralism. In general, the northern rangelands have land systems with higher carrying capacities than those in the southern rangelands.

Potential carrying capacities were estimated in cattle units (CUs) in the northern rangelands (Kimberley and Pilbara) and dry sheep equivalents (DSEs) in the southern rangelands. Note that a CU in the northern rangelands was based on a 450 kg steer as standard, but in the southern rangelands was based on a 400 kg steer. This means that in the north, 1 CU is the equivalent of 8.4 DSE, and in the south is the equivalent of 7 DSE.

As the northern definiton of a CU is the same as the Australian standard definition of an animal equivalent (AE), DPIRD will use the AE unit instead of the CU in the north, and show the old CU and the new AE unit conversions from DSE in the south (Table 2) until the industry and the relevant agencies agree on the change.

The PCC values in the northern rangelands are derived from the Report card on sustainable natural resource use in the rangelands of Western Australia and adjusted by the change identified in the Petty et al 2018 report – a 6% increase in the Kimberley and 12% increase in the Pilbara (Potential carrying capacity review, Spektrum Consulting report for Landgate). The Petty report did not cover the full southern rangelands, so the PCC has been left as in the Report Card.

| Region | PCC | CCC |

|---|---|---|

| Kimberley (northern) | 874,924 AE | 584,160 AE |

| Pilbara (northern) | 282,442 AE | 202,630 AE |

| Southern rangelands | 541,800 CU | 386,500 CU |

AE = animal equivalent; DSE = dry sheep equivalent; CU = cattle unit

Assessing change

Drivers for change in the rangelands

The WA pastoral rangelands have highly variable landscapes, soils, vegetation, and climatic conditions. The 3 primary drivers of change across all WA rangelands are:

- seasonal quality

- grazing pressure

- fire.

Seasonal quality is the amount and distribution of rainfall and its interaction with vegetation to determine grazing values. Climatic variation within and between years is a major concern for management.

Grazing pressure is the demand–supply ratio between forage needs of herbivores and the forage supply in a pasture at a specific time. The aim of management is to match grazing pressure to production and recovery of rangeland vegetation.

Fire is a naturally occurring hazard, especially in the northern rangelands, with limited management options.

The interaction of drivers of change

The interaction between seasonal quality and grazing pressure is an important interaction for pastoral management. This complex interaction may take many seasons to express changes in some of the pastoral resource themes:

- rangeland vegetation condition: from pastoral station assessments

- plant population change at the regional level: from the WARMS data

- vegetation cover: from remotely sensed data

- soil erosion: from pastoral station assessments

- soil organic carbon: from modelling.

Fire causes rapid changes to several of the themes and requires specific fire management for recovery.

Interpreting change

The status and trend of pastoral rangeland resources is based on the continued use of those resources for livestock production without causing a loss of land capability. For example, an increase in unpalatable perennial grasses may be interpreted as a decline in pastoral condition from a production perspective, whereas the greater soil cover and protection from erosion provided by the additional (unpalatable) perennial grasses might improve landscape function.

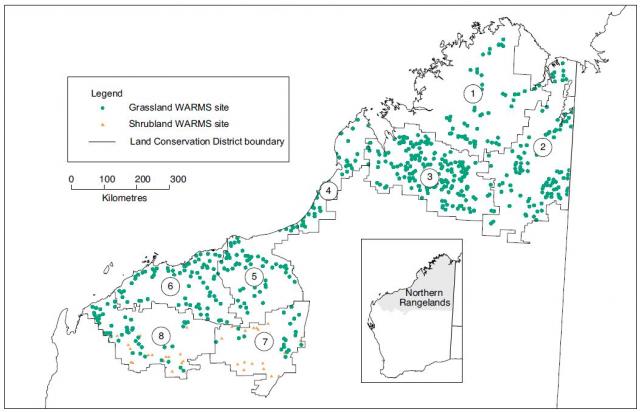

The department uses the WARMS sites to assess perennial plant population change at the regional scale. WARMS comprises a set of fixed sites on representative areas of pastoral lands (including 60 sites on 27 former pastoral stations) and provides an indication of change at a regional or vegetation-type scale, not at the pastoral lease scale. WARMS uses permanent ground-based sites on which perennial vegetation (shrubs and grasses of most value to pastoralism) and soil surface characteristics are assessed.

There are 633 grassland sites mostly in the northern rangelands, and 989 shrubland sites, mostly in the southern rangelands (Figures 12 and 13). Grassland sites are assessed every 3 years and shrubland sites are assessed every 5 years.

Information from these sites is aggregated to indicate changes in plant populations, which is generally expressed as increased, stable or decreased populations of desirable perennial plants.

Change in pastoral resource condition and trends

The latest assessment of condition and trends in the 5 themes mentioned above is in the Report card on sustainable natural resource use in the rangelands of Western Australia.