Avocado flowering basics

Suggested benefits of cross-pollination for avocados include higher yields and more robust fruit, particularly in years when the climatic conditions are less favourable for good pollination, plus some insurance against the threat of climate change. However, it is not simply a case of choosing a type B flowering variety to place into the Hass orchard (type A flowering variety).

The flowering cycle of the avocado (Persea americana) is well documented, as is the impact of temperature on this cycle (Sedgley and Annells 1981, Sedgley and Grant 1983, Sedgley and Alexander 1983).

In the South-West of Western Australia temperatures during flowering are sub-optimal for true expression of the avocado flowering cycle. Therefore, it is not only essential to ensure that as a minimum, the chosen variety will flower at a complementary time to Hass, but also important to determine that the flowering sequences of the male and female functional stages are indeed complementary under prevailing conditions. It is of commercial interest to predict the likelihood of the chosen type B variety to set reasonable crops.

Flower monitoring

To determine the flowering time of a range of potential cross-polliniser varieties, growers were contacted to identify locations with suitable varieties. The South-West is almost an exclusive Hass growing region and as type B flowering varieties are not noted for setting high yields in cool climates, there were limited varieties and locations to choose from. Table 1 lists the varieties grown at the sites monitored.

At each site, the trees were monitored on a range of dates for the total flowering potential that had opened (0% is no flowers yet opened, 50% is half the flowers opened and half yet to open and 100% is all flowers opened — flowering is finished). At the same time, the varieties were occasionally observed at varying times during the day to monitor the actual flowering stage (active female or male) and weather conditions.

| Location | Variety |

|---|---|

| Margaret River (1 site) | Hass |

| Bacon | |

| Edranol | |

| Ettinger | |

| Fuerte | |

| Sharwil | |

| Shepard | |

| Pinkerton | |

| Wurtz | |

| Manjimup (2 sites) | Hass |

| Fuerte | |

| Zutano | |

| Reed | |

| Pemberton (2 sites) | Hass |

| Ettinger |

Results

Flowering timing

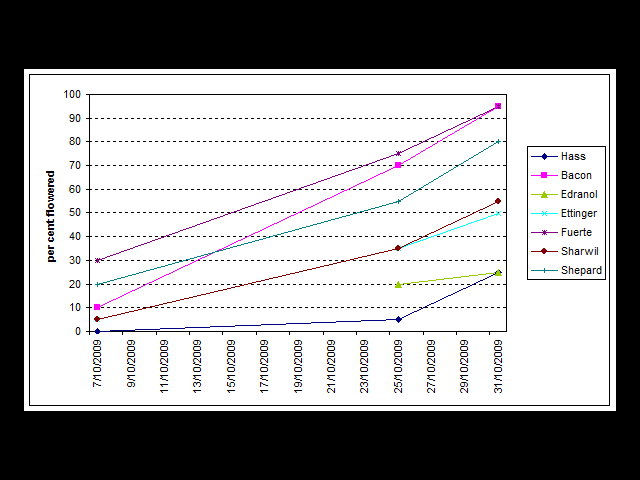

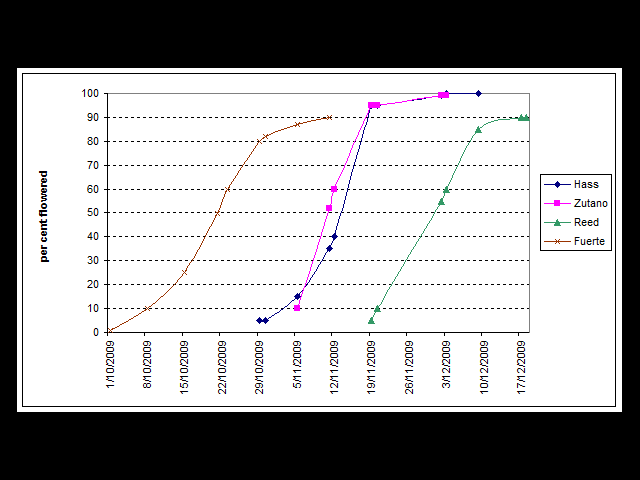

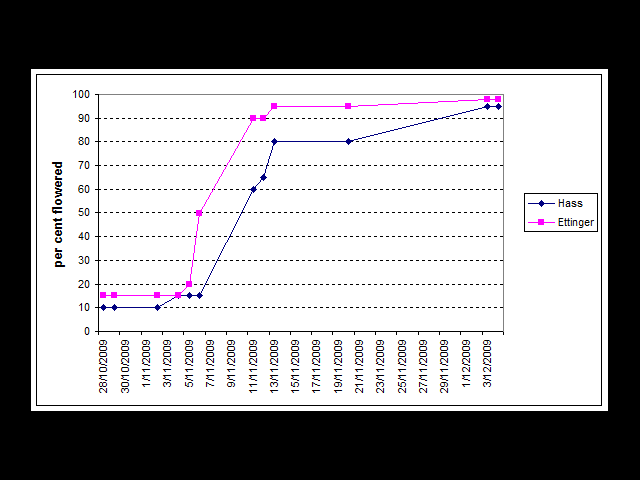

Flowering observations demonstrated differences in the timing of the varieties as shown in Figures 1, 2 and 3.

- Bacon, Fuerte and Shepard were early season flowerers.

- Edranol, Ettinger, Hass, Sharwil and Zutano were mid-season flowerers.

- Reed (another type A variety) was a late season flowerer.

Due to the protracted nature of avocado flowering in this region, all varieties had some degree of cross-over. Edranol, Ettinger, Sharwil and Zutano demonstrated a closer timing to Hass than Bacon, Fuerte and Shepard (Table 2).

It is important to note that trees of Edranol, Ettinger and Zutano were less than four-years-old which may have affected flowering. The timing of flowering of Hass was fairly similar at all monitored locations.

| Variety | Flower timing in relation to Hass |

|---|---|

| Edranol (trees less than 4-years-old) | Good |

| Zutano (trees less than 4-years-old) | Good |

| Ettinger (trees less than 4-years-old) | Slightly earlier |

| Sharwil | Slightly earlier |

| Bacon | Earlier |

| Fuerte | Earlier |

| Shepard | Earlier |

Flowering sequence

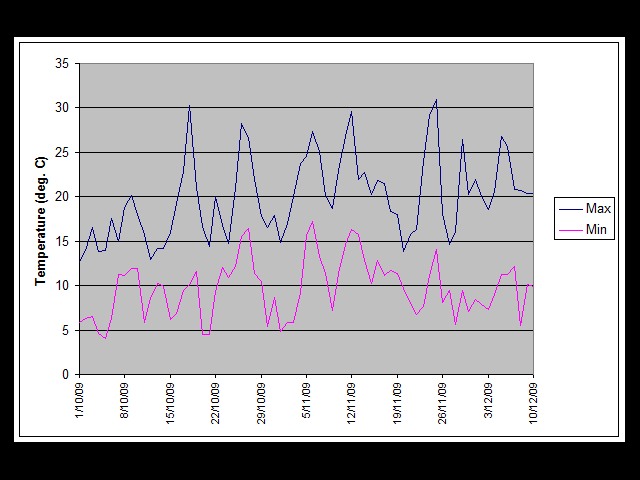

The timing of the male and female functional stages of all varieties varied throughout the monitoring period, often not conforming to the standard flowering sequence. Both the time of flower opening in general and the flowering cycle were delayed by low temperatures, particularly for type B varieties. During flowering, temperatures were regularly lower than the ideal 25/20°C maximum/minimum cycle (Sedgley and Annells 1981), and shown in Figure 4.

The type B flowers were particularly affected by the variable temperatures. The female functional stage often was not being seen during the early flowering period when temperatures were low. It was occasionally recorded not opening until late afternoon, after 5pm (1700 hours) and sometimes appearing to remain open until the next morning. The male functional stage was far more prevalent and often seen throughout the day.

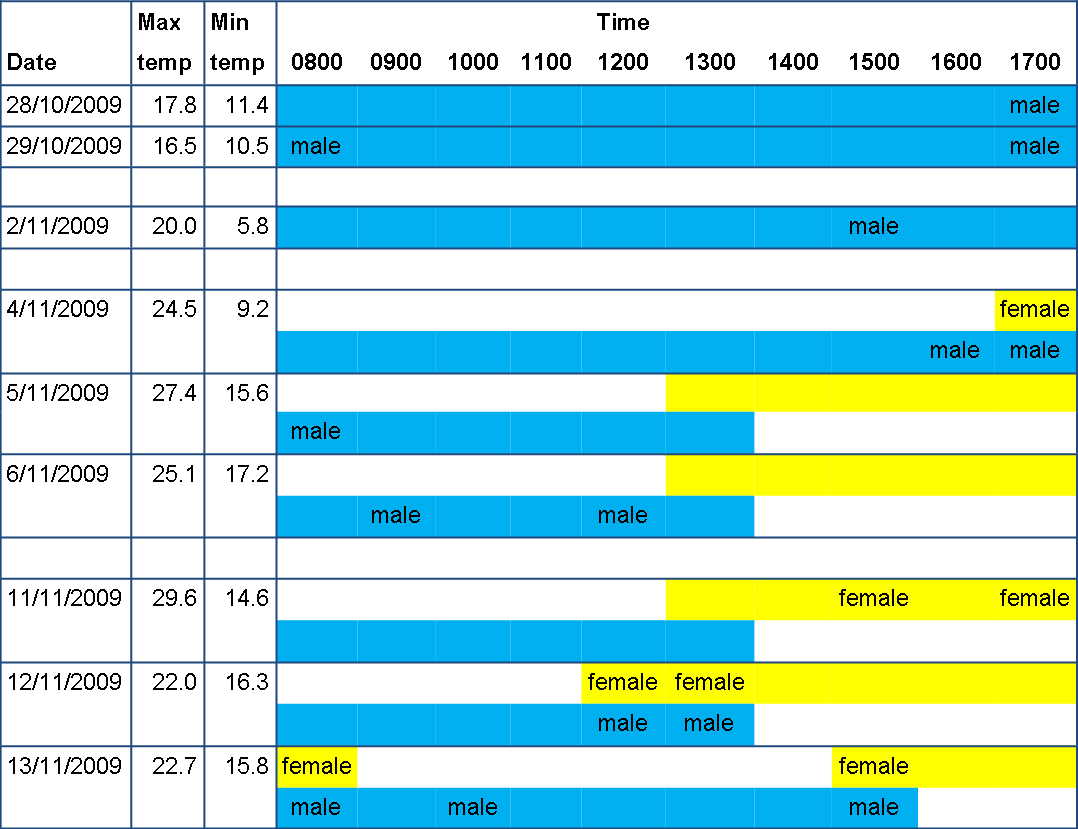

Figure 5 shows the recorded opening flower stages for Ettinger, a type B variety.

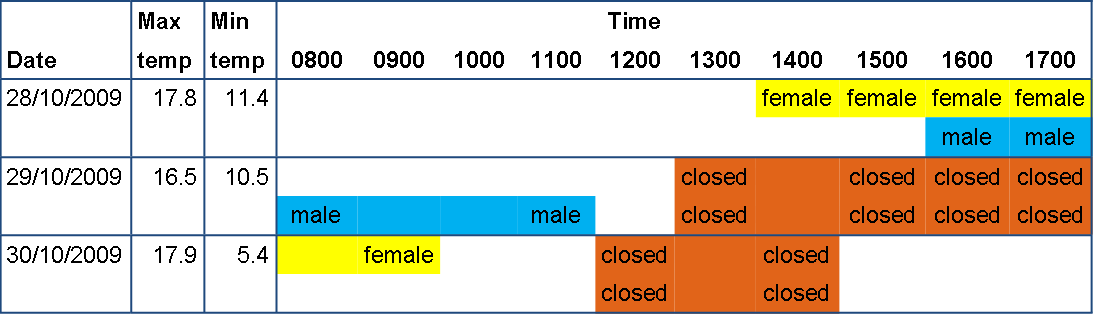

The Hass flowering sequence was also affected by variable temperatures experienced during the flowering period. During the initial period of flowering when the average maximum temperature was below 20°C and the minimum temperature was below 10°C, the opening of the stages was so affected that the flowers in one period opened as functionally female in the afternoon and functionally male the next morning, essentially mimicking the type B timing cycle (Figure 6).

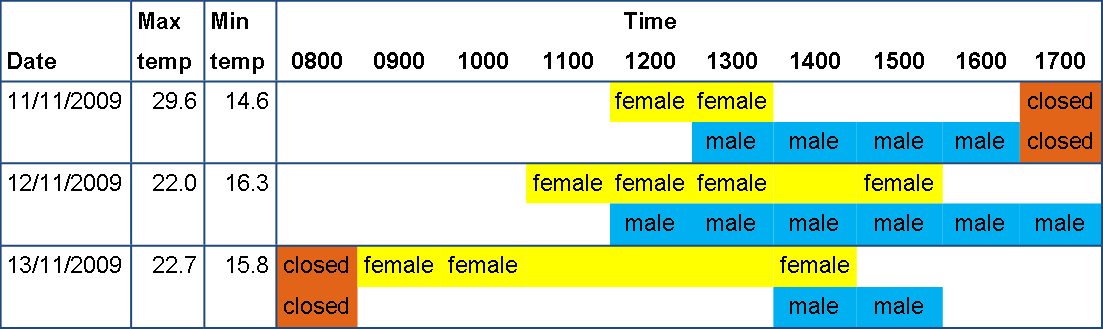

Once the temperature increased closer to 25/15°C maximum/minimum, the flowering cycle started to behave more as expected with some overlap period in the middle of the day (Figure 7). This normal sequence was quickly lost again with any drop in temperature. During the Hass flowering in 2009, there were only a few short periods of two to three days of near preferred temperatures (see Figure 7).

Conclusions

The collected data demonstrated that under the conditions during flowering in 2009, there were periods when both functionally male and female flowers could be found within a stand of Hass trees. However, this was not always the case. As the weather regime experienced during flowering was not ideal for effective pollination, it seems reasonable to consider increasing the likelihood of functionally male flowers being open and available for pollinators to visit at the same time as functionally female flowers are open on Hass.

The type B flowers were particularly affected by low temperatures with the female functional stage regularly not being seen during the day. The male functional stage was far more prevalent and often was seen throughout the day. While this will impact on the type B varieties' capacity to set reasonable crops of their own, it does mean they are far more likely to have functionally male flowers open when the Hass flowers are open as functionally female. Therefore, their potential to act as effective cross-polliniser varieties would appear to be enhanced rather than reduced by this flowering delay, particularly given the variable timing of the female functional stage of the Hass flowers. It would appear that provided flowering is occurring at the same time, the likelihood of being a potential cross-polliniser is high.

From the limited dataset, it appears that there are reasonable periods of cross-over between the flowering periods of all the evaluated type B varieties and Hass. However, a closer matching of flowering was found in 2009 with Edranol, Zutano, Ettinger and Sharwil.

Caution should obviously be exercised when interpreting a single year of data, particularly since flowering is so heavily influenced by weather. But while there are limited recordings from this evaluation and they were not contiguous, they generally concur with previously reported findings (Sedgley and Annells 1981, Sedgley and Grant 1983, Sedgley and Alexander 1983). As a result, a reasonable degree of confidence can be had in the results.

Further issues

While the data has demonstrated the potential of the evaluated type B varieties to provide pollen for variety Hass, it has not evaluated whether any cross-pollination occurred or if it is really required. While there were periods when there was no male/female cross-over within the Hass tree and there was cross-over with another variety, this also coincided with periods of weather that were not particularly conducive to good pollination. The availability of pollen may not be the only limiting factor for pollination to occur.

An extra complication, not investigated, is the effect of rain on both pollen release and bee activity. There is also the issue of bee preference to visit either male or female functioning flowers, rather than both, something that was noticed but not effectively monitored.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to David Rankin who collected the flower data for Margaret River. Thanks also to the growers who allowed regular access to their orchards for monitoring of avocado flowers – Wayne Edwards, Dean French, William French and the Manjimup Horticultural Research Institute.

This report was previously published as Appendix H in ‘Improving technology uptake in the WA avocado industry’, a final report for Horticulture Australia Limited project AV06002 funded by the Agricultural Produce Commission Avocado Growers Committee, Horticulture Australia Limited and Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia. The complete final report is available electronically via Avocados Australia web site (member services login) or Horticulture Innovation Australia (abstract or hard copy for purchase).

References

The following references and many more on the subject are available electronically via avocadosource.com, an extensive internet database of avocado information from around the world — hosted by the Hofshi Foundation.

Sedgley, M and Annells, CM 1981, 'Flowering and fruit-set response to temperature in the avocado cultivar Hass’, Scientia Horticulturae, vol. 14, pp. 27-33.

Sedgley, M and Grant, WJR 1983, 'Effect of low temperature during flowering on floral cycle and pollen tube growth in nine avocado cultivars', Scientia Horticulturae, vol. 18, pp. 207-213.

Sedgley, M and Alexander, DMcE 1983, 'Avocado breeding research in Australia', California Avocado Society 1983 Yearbook, vol. 67, pp. 129-140.