What are the signs of eperythrozoonosis in sheep?

Signs of eperythrozoonosis include:

- ill-thrift

- anaemia (pale gums)

- jaundice (yellow gums)

- dark red urine

- death (particularly following a stress event such as yarding).

The Mycoplasma ovis bacterium infects the red blood cells of the animals, prompting the spleen to attempt to clear the infection by destroying the diseased blood cells. It is this excessive destruction of the blood that leads to anaemia, jaundice and death. Disease outbreaks can last for 14 to 28 days.

It is important to diagnose the disease correctly because the stress of moving severely anaemic animals can lead to high death rates. Other causes of ill-thrift, anaemia, jaundice and death must also be excluded and they include conditions such as infection with barber’s pole worm, copper deficiency or vitamin B12 deficiency.

Susceptible animals

Not all infected sheep will show signs of the disease. The immune system of some sheep will effectively fight off the infection and rid the bloodstream of the organism. Other animals’ immune systems will not completely eliminate the organism, but will keep it at such a low level that it does not cause disease. Such animals may stay infected for life. They may relapse into clinical disease when stressed, or suffer from recurrent bouts of low-grade anaemia every 2–4 months. These ‘carrier’ animals are the most likely source of infection for other sheep. A reservoir of infection is probably maintained in breeding ewes.

Outbreaks of disease can vary in severity, and this is influenced by the strain of M. ovis involved and the health of the sheep.

The disease is usually more severe in:

- young sheep

- sheep not previously exposed to infection

- sheep with other illnesses (e.g. worms, malnourished)

- pregnant ewes.

How is eperythrozoonosis spread?

Eperythrozoonosis is spread by the transfer of infected red blood cells from one animal to another. Many outbreaks occur 4–6 weeks after marking, mulesing or shearing. The disease may also be spread by management procedures such as vaccination (re-using the same needle), eartagging, bloodsucking insects (e.g. mosquitoes and midges) and flies on wounds.

How common is the disease?

The majority of infected sheep develop no visible signs of disease. It is possible to have infected animals on your property and not know it. Historical surveys by the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD) have shown:

- About 5% of weaner sheep in WA may have M. ovis infection.

- Infection could be present on about 50% of farms.

- Infected farms are more likely to occur in the northern agricultural region surrounding Geraldton and throughout the great southern and south coastal agricultural regions.

Outbreaks of this disease have been diagnosed most frequently during September and February. Rural veterinarians in WA believe that the disease occurs most commonly during spring.

Historical surveys in Victoria found that 90% of farms had M. ovis infection and 50% of adult sheep tested positive for infection. In Queensland, 68% of farms surveyed had the infection and infection within a flock varied from 2–80%. In Tasmania, 45% of adult sheep tested positive for infection.

How is eperythrozoonosis diagnosed?

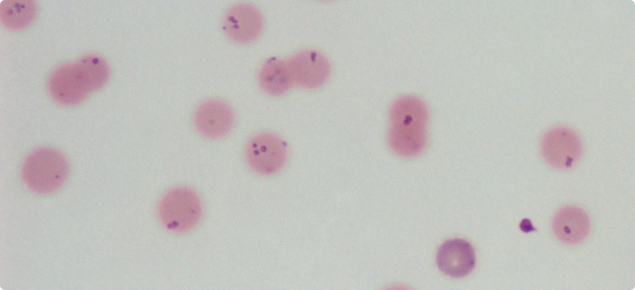

Eperythrozoonosis is diagnosed by laboratory serology testing and/or by identifying the bacteria on blood films prepared from sheep. It may sometimes be difficult to detect the organism in blood because by the time signs are visible, the majority of infected cells have been removed. Thus it is important to take samples early in the course of the disease and to sample 10 visibly affected and 10 apparently unaffected sheep.