Introduction

The beet cyst nematode (Heterodera schachtii) can cause considerable yield loss in brassica vegetable crops (cabbages, Chinese cabbages, cauliflowers, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, turnip, radish and swede), as well as to beets (red and silver), rhubarb and spinach, by severely damaging root systems, especially during summer. This nematode also infects many common weeds such as wild turnip, shepherd’s purse, fat-hen and portulaca.

Entire fields can be infested, but infestations are most often in localised patches. Natural movement is limited so spread is often in an elliptical pattern of poorly growing plants in the direction of machinery movement. Over time, the smaller areas of infestation will enlarge and spread.

Beet cyst nematode can parasitise plants of all ages. Seedling attack can result in severe injury or even plant death. Damage is less notable when older plants are attacked.

Nematodes feed on plant roots, reducing the plant’s ability to take up nutrients and water. Therefore above-ground symptoms look like nutrient deficiency or drought — reduced stand, poor growth, stunting, yellowing and wilting (Figure 1).

An infested crop contains smaller plants of reduced value and quality and will compete poorly with weeds.

Roots attacked by beet cyst nematode often appear ‘bearded’ or ‘whiskered’ due to excessive development of fibrous roots as the plant attempts to combat nematode damage. Impacted root vegetables have smaller storage roots and may also develop abnormal swellings or lumps.

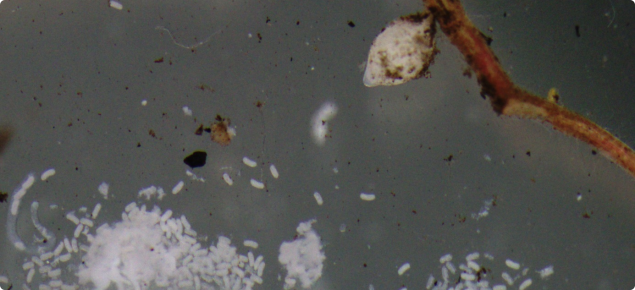

The most evident sign of beet cyst nematode is the appearance of glistening white-yellow bodies about the size of a pin head attached to the fibrous roots. These mature and harden to produce a light-brown to reddish-brown cyst (Figure 2).

Life cycle

Cyst nematodes are extremely problematic because they can persist for years in soil without a host. Their remarkable persistence is due to their ability to produce a cyst, which is the hardened dead body of the female nematode that surrounds and protects the eggs from adverse environmental conditions.

Each cyst contains several hundred dormant eggs which hatch slowly over years when stimulated by moisture and root exudates from growing host plants (Figure 3).

Juveniles are attracted to the roots, infecting near the tips, causing roots to branch profusely. They feed within the roots and develop into adults.

When mature, males emerge from the roots while females remain sedentary. Females become lemon-shaped, protrude from the root surface and can be seen as small white-yellow dots about the size of a pin head. The female dies and her body, which contains many eggs, hardens to form a cyst. The cyst detaches from the roots to remain in the soil.

Development from root penetration to the mature cyst takes about four to eight weeks, depending on temperature. Optimum temperature for growth and reproduction is 21 to 27°C. Several cycles may occur during the growth of the host plant and greater damage may occur in summer when soils are warmer and plants tend be under increased environmental stress.

As many as five generations per season are possible in warmer climates, when plants are re-invaded by freshly hatched juveniles within one growing season.

Control

These nematodes are soil-borne so are usually introduced in contaminated soil on boots, hands, crates, tools and machinery. It is also important to ensure that infested seedlings are not planted, as they will suffer severe damage as well as aiding the introduction or spread of nematodes and re-infecting treated areas.

Once an area is infested, the nematodes can be managed but not eradicated so the best control method is to practise good hygiene.

Pre-planting soil treatment using nematicides is not 100% effective as the protective cysts are tough and can be widely distributed within the soil. Furthermore, these chemicals can be subject to enhanced biodegradation and become less effective when the same chemical is applied repeatedly. Biodegradation is the development of soil organisms that degrade the nematicide.

Nematicides are particularly toxic, so need to be used with care, adhering to withholding periods and according to registered usage for each crop. Information on currently registered chemicals for BCN management can be found at the APVMA website.

Nematode populations can increase rapidly under successive host crops, so an initially low population can increase to high levels by the end of a growing season.

Rotation with a non-host crop such as legumes, corn, cereal, onion or potato can aid in reducing nematode levels. Three to four years may be required and crop rotation is more useful in preventing population build-up than in reducing already high populations.

Weeds can provide a reservoir of infection, contributing to build-up and carry-over of nematodes. Fallow also needs to be weed-free to be effective.

Planting crops when soil temperatures are lower as nematodes are less active and reproduce more slowly can reduce damage. Seedlings are more prone to severe damage than older plants.

AGWEST Plant Laboratories can test soil and/or plant roots for nematodes. To obtain submission forms and full sampling instructions contact +61(0)8 9368 3721 or +61(0)8 9368 3333.

Acknowledgement

The original information for this webpage was authored by Vivien Vanstone.