Livestock disease investigations protect our marketsAustralia’s ability to sell livestock and livestock products depends on evidence from our surveillance systems that we are free of particular livestock diseases. The WA livestock disease outlook – for vets summarises recent significant disease investigations by Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD) vets and private vets that contribute to that surveillance evidence. |

|

Recent livestock disease cases in WA

Private vet investigates illthrift and deaths in Merino ewes in the South-West

- A private vet received a subsidy under the Significant Disease Investigation Program to investigate a case of illthrift, weakness and deaths in 4-5-year-old Merino ewes.

- The producer reported 50 ewes from a flock of 2300 lambing ewes had been found weak, recumbent and dead. The flock was closed, other than to rams, and the flock had been provided with adequate vitamin and mineral supplementation.

- The private vet conducted a post-mortem on an emaciated ewe, which showed empty intestines, watery diarrhoea and enlarged lymph nodes. A full sample set from this animal, and blood and faeces from another emaciated ewe, were collected and submitted to the DPIRD laboratory, with the private vet suspecting ovine Johne’s disease (OJD).

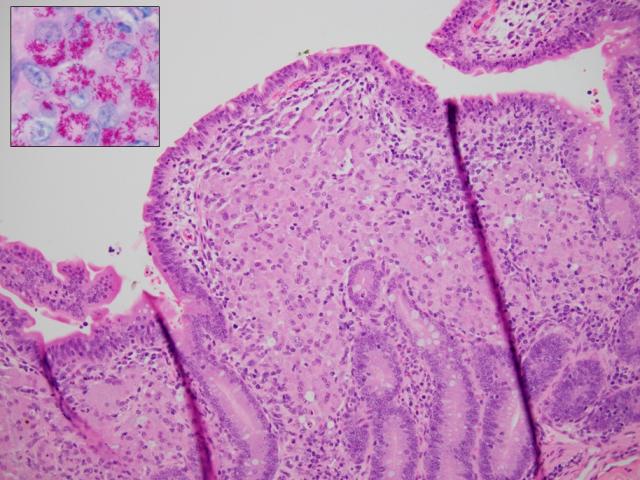

- On biochemistry, one ewe was severely hypoalbuminaemic, which is consistent with a protein-losing enteropathy. Histopathology of the ileum, jejunum and caecum showed a severe granulomatous enteritis and typhlitis, with myriad acid-fast organisms within the lesions, confirming the diagnosis of OJD (see Figure 1).

- Reaching a diagnosis allowed the private vet to work with the producer to manage the disease in their flock. For management information, see the DPIRD OJD webpage.

- Key points about OJD: OJD is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (commonly referred to as Mycobacterium paratuberculosis). The bacterium infects sheep, goats and deer, and after a long incubation period (years), causes a fatal wasting disease. The biggest risk of introducing infection into a flock is through the introduction of sheep (purchased, agisted or strays). See the DPIRD webpage on OJD risk management for more information.

- For a summary of the subsidies available for disease investigations for vets and producers, see the DPIRD surveillance incentives webpage. Printed copies are available by emailing waldo@dpird.wa.gov.au.

Reportable diseases ruled out in a flock of backyard chickens

- Last month, a backyard chicken owner reported that two adult Australorp hens had died from their flock of 30 on Perth’s outskirts.

- The illness progressed over four days, with birds first showing lethargy, followed by discolouration of the comb, green diarrhoea and death.

- The owner contacted the DPIRD laboratory, and one chicken was submitted for post-mortem. The post-mortem showed a large mass of consolidated yolk material in the oviduct, with histopathology confirming a chronic and severe oviduct infection (salpingitis), with likely haematogenous spread of bacteria causing pneumonia and hepatitis.

- Given that the clinical signs in this case shared some signs of the reportable diseases avian influenza and Newcastle disease, PCR testing for these viruses was conducted on tracheal and cloacal swabs. All samples returned negative results. Laboratory fees were paid by DPIRD, as the investigation was able to rule out the involvement of reportable diseases.

- Signs consistent with reportable diseases in poultry should always be reported to your DPIRD field vet or to the Emergency Animal Disease hotline on 1800 675 888.

- DPIRD has some useful online resources for poultry disease investigations, including an overall approach to investigating disease in poultry and a chicken post-mortem guide.

- For a summary of the subsidies available for disease investigations for vets and producers, see the DPIRD surveillance incentives webpage. Printed copies are available by emailing waldo@dpird.wa.gov.au.

Private vet investigates abortion in Angus heifers in the Great Southern

- In September in the Great Southern, 15 of 30 heifers and 5 of 210 cows in an Angus herd had failed to calve despite positive pregnancy testing.

- A private vet attended the property and suspected early abortion. The vet submitted blood samples with differential diagnoses including neosporosis, pestivirus and the zoonotic disease leptospirosis.

- Serology at DPIRD found three samples were positive for bovine herpesvirus-1. Antibody testing cannot distinguish between naturally infected and vaccinated animals, so vaccination history must always be taken into account when interpreting these results.

- In this case, the diagnosis was presumed bovine herpesvirus-1. This virus, which also causes infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, can be responsible for abortions in previously unexposed cows if infected during pregnancy.

- Testing for other infectious causes of abortions, including bovine brucellosis and leptospirosis, was negative.

- For more information, see the DPIRD webpage about the many causes of infertility and abortion in cows.

- For a summary of the subsidies available for disease investigations for vets and producers, see the DPIRD surveillance incentives webpage.

In spring, watch for these livestock diseases:

Disease, typical history and signs | Key samples |

Polioencephalomalacia (PEM) in sheep and cattle

| Ante-mortem:

Post-mortem:

|

Worms in sheep and cattle

| Ante-mortem:

Post-mortem:

|