Description

Tall wheatgrass (Thinopyrum ponticum) grows naturally in the Balkans, Asia minor and southern Russia. It is a deep rooted, drought tolerant, summer active, tussock-forming temperate perennial grass that grows to a height of 2 metres.

Leaves are up to 50cm long, 4–8mm wide, hairless or with scattered hairs, with a scabrous point and margins (Figure 1). The seed head is an unbranched spike to 30cm long that breaks up at maturity, the spikelet placed with the flat side to the axis.

Older non-current synonyms are Thinopyrum elongatum, Agropyron elongatum and Lophopyron elongatum.

Tall wheatgrass is a warm season C3 species, is not frost sensitive, and is well suited to southern Australia.

The two common tall wheatgrass cultivars, Dundas and Tyrrell, have similar yields and salinity tolerance across a range of saline soils. Dundas is a selection from within Tyrrell for enhanced leafiness, and improved feed quality and diseas resistance.

Benefits

Production

- TWG is highly productive with good digestible energy and protein levels if kept vegetative and leafy, but will revert to low nutritive value and palatability (less than a maintenance feed) if allowed to grow rank and set seed.

- Established plants tolerate hard grazing.

- Nitrogen fertiliser will greatly increase production.

- It is an alternative pasture where ryegrass staggers and phalaris toxicity are problems in early autumn.

Tall wheatgrass can produce significant biomass given sufficient summer moisture. Effectively managed tall wheatgrass pastures are more than capable of filling the summer/autumn feed gap, while most other pastures are dormant or dead.

Yields of 7t/ha/yr are possible on soils of moderate subsoil salinity, but these increased to 13t/ha/yr in soils of low subsoil salinity. Tall wheatgrass pastures sown with a companion legume are capable of increasing stocking rates from 0.5DSE/ha to 12DSE/ha in suitable environments.

Tall wheatgrass declines in quality over late summer, even when kept short and green.

Tall wheatgrass pastures can be used to make good silage, although the rapid decline in pasture quality with plant maturity means that it is more difficult to reliably produce good hay.

Reducing surface salinity and waterlogging

Tall wheatgrass can reduce topsoil salinity, and salt movement from a site by preventing the capillary rise of salts to the surface.

Soil will be drier in autumn and this delays the onset of winter waterlogging under tall wheatgrass pastures. This provides better condition for other species such as balansa clover.

In the Great Southern Region of WA measurements, winter waterlogging occurred a month later on tall wheatgrass – balansa pasture compared to balansa–only pasture. The duration of waterlogging on tall wheatgrass-balansa pastures was also reduced to a third of the time of the balansa–only pasture during a growing season (May–October).

Amenity and environmental

Revegetating saltland Improves visual amenity for many farmers – sparse sea barleygrass transforms to a productive pasture.

The SGSL initiative showed that tall wheatgrass-based pastures have biodiversity values intermediate between bare salt scalds and remnant native vegetation as measured by landscape functional analysis.

Problems

Tall wheatgrass has a high environmental weed risk rating for medium to high rainfall southern Australia, which is where it is best suited to grow. We recommend not using tall wheatgrass where it can spread by seed into non-target areas. See management of tall wheatgrass for more information

Suitable sites for tall wheatgrass

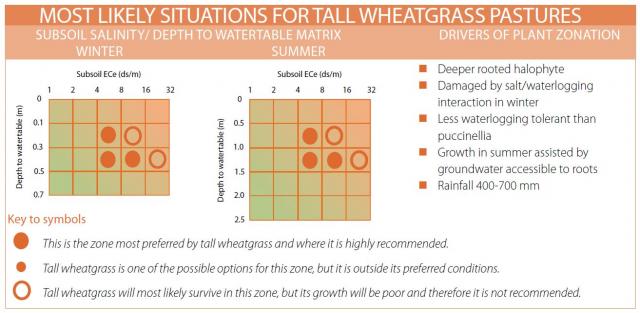

Suitable site factors for tall wheatgrass are summarised in Figure 2.

Common indicator species

Tall wheatgrass thrives in conditions that also favour buck’s horn plantain, sea barleygrass and spiny rush.

Tall wheatgrass is unlikely to be found in saltier environments where samphire dominates, or in areas that have high waterlogging or inundated for extensive periods during the warmer months. SALTdeck cards assist with the identification of the 50 most common saltland species.

Salinity and waterlogging tolerance

Mature plants of tall wheatgrass have relatively similar salinity tolerance, but lower waterlogging tolerance, than puccinellia. However, tall wheatgrass is more persistent and productive at better drained sites.

Tall wheatgrass does not persist in soils that are waterlogged over spring and into summer. Grows in soils that have low to moderate salinity. (see below).

Soil and climate conditions

- The minimum annual rainfall for tall wheatgrass is reported as about 425mm, although it is generally regarded as a pasture for higher rainfall zones, up to as much as 800mm.

- It is frost tolerant and recovers well after frost damage.

- It does not persist in soils that have high waterlogging over spring and into summer, but it does persist in soils subject to low to moderate waterlogging in winter that dry out over summer.

- Tall wheatgrass is tolerant of acid and alkaline soils.

- It grows particularly well in soils of moderate subsoil salinity (ECe 4-8dS/m), soils often supporting sea barleygrass and buck’s horn plantain. It can tolerate soils in which the salinity of the topsoil reaches summer ECe values of 20dS/m, providing it can still access less saline moisture from the subsoil in late spring.

Waterlogging and surface water management

Tall wheatgrass is tolerant of moderate waterlogging in the cool season and brief periods of inundation, provided some of the plant is above the water level. Improved surface drainage should improve its growth during periods of excess water.

Surface drainage can improve access to the site for establishing the pasture. However, deeper groundwater drains may deprive the pasture of moisture from deeper in the soil profile in early summer.

Establishing and managing tall wheatgrass

Dundas is now generally regarded as the variety of choice, except where farmers are harvesting their own seed from old Tyrrell stands.

Site preparation

Fence the site

It is best to fence to control grazing as tall wheatgrass does not make strong early growth, and is often sown into soil that soon becomes very wet and vulnerable to pugging by livestock. Temporary electric fencing may be sufficient, particularly for small areas where separate grazing is impractical.

Drain surface water

If waterlogging is likely to present a problem at sowing, shallow drains can be used to remove excess water. Diversion or reverse interceptor banks will reduce the movement of runoff water onto the area, but care should be taken that these banks do not go through sodic soil that might give way and lead to erosion. When designing drainage systems it is important (and possibly a legal requirement) to consider the impact of water disposal on downstream biodiversity and on other landholders, and ensure that no harm will be done.

Prepare a seed bed

The soil should be lightly cultivated or scarified prior to the break of the season. The time without vegetation should be minimised to reduce the capillary rise of salts to the surface.

Weed and pest control

It is important to control weeds, especially annual grasses, most often sea barleygrass, by spray topping the previous spring. It may still be necessary to kill germinating weeds prior to sowing with a knockdown herbicide because germinating annuals will easily out-compete tall wheatgrass seedlings.

Tall wheatgrass should not be sown with annual legumes, because the vigour of the annuals will suppress the growth of the tall wheatgrass seedlings, particularly on areas of low salinity. Buck’s horn plantain and summer-growing salt-tolerant perennial grasses do not represent strong competition for tall wheatgrass, and are useful within a tall wheatgrass-based pasture. A full kill of these species is not necessary to establish tall wheatgrass.

Red-legged earth mite (RLEM) can challenge wheatgrass during establishment. The Timerite® program is an excellent tool for controlling RLEM, but timely chemical application can be difficult on very wet sites.

Sowing pasture mixes

Single species pastures are the easiest to manage, and since the productivity from tall wheatgrass is

very management dependent, this is an important consideration.

Where a site suits puccinellia and tall wheatgrass, we recommend assessing the site for salt and waterlogging, and sowing each species on its preferred zone. Sow a species mix only where these zones are likely to overlap.

A tall wheatgrass/puccinellia mix poses significant grazing management compromises. Tall wheatgrass should be grazed heavily over spring and summer to prevent clumpiness, puccinellia is best left standing over this period and then grazed down in autumn.

Companion species can include puccinellia, balansa clover, strawberry clover, persian clover, tall fescue and lucerne, depending on site salinity, waterlogging, average rainfall and other site conditions. The grasses help to balance the pasture by extending the grazing season and taking advantage of variations in soil condition across the paddock. The legumes contribute valuable fixed nitrogen to the grasses and protein to the grazing animals.

Balansa and Persian clovers are generally compatible with tall wheatgrass, and increase production by supplying nitrogen. Balansa is particularly adapted to waterlogging, but neither species persists in soils of moderate salinity.

Direct-drill these clovers the year after the tall wheatgrass is established, to ensure that the perennial has established well. Strawberry clover – a perennial legume with high tolerance of waterlogging and low to moderate tolerance of salinity – can be sown with tall wheatgrass in high rainfall environments (see Pasture legumes and grasses for saltland).

Typical recommended mixes include:

• ECe: <5dS/m: TWG, tall fescue*, strawberry and balansa clovers**.

• ECe: 5–10dS/m: TWG, strawberry and balansa clovers.

• ECe: 10–20dS/m: TWG and puccinellia.

* Victorian trials have shown that Resolute and Advance tall fescue will germinate and grow at ECe levels up to approximately 8dS/m, losing up to 50% of productivity at this higher salinity level.

** The early-flowering Frontier balansa has the advantage that it can set seed before salinity levels escalate in spring.

Seeding rates

Tall wheatgrass is usually sown at 15–20kg/ha if sown alone. We recommend testing seed germination in the year of sowing, as the seed loses viability rapidly after two years.

The recommended sowing rates below assume a germination of 50–90%.

We recommend the rates below for sowing pasture mixes:

- tall wheatgrass at 10–15kg/ha with puccinellia at 4–10kg/ha.

- 1tall wheatgrass at 4-5 kg/ha in a shot-gun mixture with other grasses or legumes which together might be medics 2kg/ha, clovers 0.5–2kg/ha, lucerne 2kg/ha, phalaris 2kg/ha.

1 This low tall wheatgrass sowing rate assumes legumes are to be sown the year following the tall wheatgrass. Weeds may be a problem at this low density.

Fertilisers and downtime

We recommend soil testing before sowing any pastures.

As with all new pastures, a soil test is advisable. Like most grasses, tall wheatgrass responds to phosphorus and nitrogen, but where other grasses typically get their N from companion legumes this opportunity is not always available to tall wheatgrass in saline conditions. Nitrogen applied in late winter or early spring will boost productivity and maintain plant palatability.

Establishment costs are about $300/ha for seed, cultivation, herbicide and fertiliser, plus a further cost for fencing which will depend very much on the size of the saline area. In addition there is the opportunity cost associated with the establishment downtime, but in most cases the opportunity foregone on unimproved saltland is very small.

Time of sowing

As with all pastures, but perhaps more so on saltland, options for sowing times are largely dependent on weather condition and the state of the paddock. These options come down to:

• Autumn sowing after the autumn break (in southern Victoria this should be before the end of April).

• Dry sowing in April if the autumn break is late (this may lead to excessive weeds).

• Spring sowing, as soon as the area is trafficable after the end of winter. This option works well in years with dry winters and extended springs, but if the area is not trafficable until late spring, there will be insufficient time for the plants to establish before the onset of higher salinity levels in summer. Sowing in spring is of course not an option if an annual such as balansa clover is to be included.

Managing tall wheatgrass

Tall wheat grass is strongly tussock forming and can quickly become clumpy, rank and unpalatable to livestock if not well managed. In addition, the clumps or tussocks can become so large as to make a paddock almost untrafficable. Keep TWG pastures short and vegetative to maximise feed value. Old rank tall wheatgrass can be rehabilitated by slashing, burning or mulching of old growth, however working in old neglected wheatgrass paddocks can be hard on machinery.

If allowed to run up to seed, tall wheatgrass can spread and colonise areas where it is unwanted, particularly along watercourses.

Management of tall wheatgrass can mean the difference between having a productive pasture contributing

significantly to a grazing enterprise, and having a troublesome paddock of tussocky unpalatable grass.

Starting from the point of establishment, managing tall wheatgrass should be seen in two phases:

- the year of establishment

- subsequent years.

Managing new stands: year 1

The year of establishment is critical for tall wheatgrass as it is not a vigorous seedling, but it does persist well once established. It will respond to nitrogen and phosphorus in spring, although N might not be economical if the pasture is to be only lightly grazed and if growing with a legume.

Careful grazing is essential in the first year to maintain leafiness and allow seed set and thickening of the pasture.

Sites with low salinity (summer subsoil ECe 2–4dS/m)

Tall wheatgrass can be grazed lightly in spring provided the site is not waterlogged and the seedlings are firmly anchored in the soil. The vigour of Balansa clover may suppress the grass in the first year. However, if balansa is sown, stock should be removed in time to allow the clover to flower and set seed during spring. Generally, some tall wheatgrass seed set should be allowed in that first year to enable the grass to thicken up.

Grazing over summer-autumn should be conservative, aimed mainly at strengthening a permanent pasture

rather than maximising immediate production. Grazing down to about 5cm will promote strong root

development and removing thatch will provide good conditions for regeneration of clover with opening rains.

Sites with moderate salinity (summer subsoil ECe 4–8dS/m)

Grazing on these sites might not be possible in the first year without damaging the poorly established grass and causing soil damage. Puccinellia, if sown in a pasture mix, will usually also benefit from a first year spell on such sites.

Managing new stands: year 2+

Nutrients

We recommend a soil test every 3–5 years to determine fertiliser needs.

Where legumes are not present, tall wheatgrass will benefit from annual applications of nitrogen at 25–50kg N/ha.

Tall wheatgrass will show limited response to N if exchangeable P levels are below a critical level. This value has not been determined for tall wheatgrass, but for many perennial grasses the critical P level is approximately 12–14mg/kg (Olsen P) or 24–28mg/kg (Colwell P). Up to 9kg P/ha (in high rainfall areas) might be needed annually for maintenance.

Grazing

Grazing management of mixed pastures containing tall wheatgrass will need to be carefully considered

where pasture species have different seasonal activities. Allowing seed set for legumes while controlling the same for tall wheatgrass involves compromises which can cause deterioration of the pasture.

Winter to early-spring grazing in non-waterlogged sites will make use of other components of the pasture mix such as balansa clover. At the first sign of balansa flowering, careful (rather than crash) grazing of the pasture is needed to ensure adequate seed set and retention of the legume base. Experience in the southeast of SA shows that moderate stocking rates during flowering (which also corresponds to a period of high growth) enables adequate seed set and regeneration.

However, the pasture composition should be monitored and where the legume component is not regenerating it may be necessary the next year to further limit or stop grazing from flowering until seed set is complete.

Once balansa clover seed set is complete (which depends on the cultivar) the stand can be crash grazed

to remove excess balansa growth and wheatgrass stems which will have started to run up to flower. Continue grazing throughout summer and into autumn to maintain a pasture height below 10cm. Stock will avoid grass that has begun to go rank. Crash grazing may remove the rank material.

Mature stands can be profitably harvested for seed.

Rejuvenating old tall wheatgrass stands

Rank stands of tall wheatgrass can be returned to production, and the weed threat can be managed, by mulching or slashing (to a height of 10cm). If these treatments leave a heavy mat which smothers pasture regrowth, burning may be a better option.

After the initial intervention grazing and management should then follow recommendations for managing new stands (year 2+).

Most old stands have no legume component which is critical for a good quality pasture. Where salinity levels allow, balansa clover seed can be broadcast with the fertiliser in early autumn. If soil conditions permit, and if rank grass is removed and some bare ground is visible between plants, balansa clover will readily germinate.

Controlling weed escape

Preventing seed set, usually by grazing down to 10cm in summer-autumn, is the key to controlling spread of tall wheatgrass from a sown site. Tall wheatgrass pastures should be fenced and contain their own water supply, to enable effective grazing management. Do not sow tall wheatgrass near creeks and waterways, remnant vegetation, plantations or roadsides.