Grazing dry summer pastures

Feed budgeting in the dry period is inherently difficult due to the variability of the quality of dry feed and the value of the subsequent portion that the sheep choose to eat. The decline rate, pasture height differences between different pasture systems and the amount of grain available in stubbles also affect the amount of energy sheep can gain from grazing dry residues.

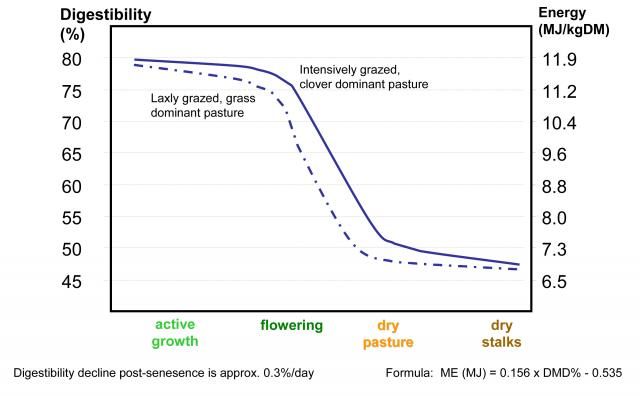

The dry residues of annual pastures like subclover, medic and serradella, along with weeds such as ryegrass and capeweed, usually have a digestibility of about 55% at the start of summer. This level can vary considerably and will decline over time, especially after hot weather and rainfall that damages the finer leaf fraction of the pasture. Most of the decline from above 70% to below 50% happens in three to six weeks, with hotter weather causing a quicker decline than cool weather.

The amount of feed that can be eaten by a sheep on a daily basis is related to the digestibility of the feed (often called quality). The lower the digestibility, the lower the feed intake by the sheep. Dry feed with a digestibility below 55% – approximately 8 megajoules per kilogram (MJ/kg) – will, at best, only maintain liveweight regardless of the feed on offer level as the sheep can’t eat more than one kilogram on a daily basis.

| Feed on offer (kg DM/ha) | 45% digestibility | 50% digestibility | 55% digestibility | 60% digestibility | 65% digestibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.8 |

| 1000 | 2.7 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 5.8 | 7.1 |

| 1500 | 4.4 | 5.7 | 7.1 | 8.3 | 9.5 |

| 2000 | 5.8 | 7.3 | 9.0 | 10.4 | 12.0 |

For young sheep, a dry annual pasture with about 50% legume content can only provide growth rates of one to two kilograms per head, per month for one to two months. This is because it is only slightly above a maintenance ration.

It is recommended that sheep are regularly assessed for condition score over the season to ‘let the sheep do the talking’ on how much and what quality of feed is being eaten.

Grazing stubbles

After six weeks in any stubble paddock it is highly unlikely that sheep will be gaining weight — rather, it is more probable that most sheep will be losing weight. Supplementary feeding is therefore essential during late summer and autumn to provide additional energy and protein for maintaining sheep liveweight, particularly of young animals or pregnant ewes.

Stubble quality and quantity varies highly from year to year and location to location. There are also large losses of edible material caused by shattering during harvest and trampling as sheep selectively graze the stubble paddocks.

The energy content of the dry plant material determines how much the stock can eat. About a quarter of fresh wheat stubble has a digestibility of more than 55%, one third has a digestibility between 50-55% and the rest is indigestible stem material. Grazing sheep are able to select the more nutritious parts of the stubble crop. Spilt grain remaining after harvest is eaten rapidly, so that even though it forms only a small proportion of the dry matter available in the stubble, grain is a high proportion of the diet selected. Once most of the grain has been eaten, sheep select the more digestible parts of the plant straw.

It is important to assess the amounts of grain available before sheep are put in stubble paddocks. A simple method to measure the amount of grain available in a stubble is to use a 0.1 square metre (m2) square — approximately 30 centimetres (cm) x 30cm. At least 20 counts on a line across each paddock at right angles to the harvest runs are needed to get an indication of the average levels of residual grains. One hundred kilograms of grain per hectare equals, on average, approximately:

- wheat and oats — 28 grains per square

- barley — 25 grains per square

- lupins — 8 grains per square

- field peas — 5 grains per square

- chick peas — 5 grains per square

- faba beans — 2 grains per square.

Top tips

- Paddocks should not be grazed after the amount of ground cover declines to 50% or less. In some situations there could be no point in grazing the stubble.

- Legume stubbles are potentially better than cereal stubbles as feed sources for young sheep, and for ewes before or during mating.

- To obtain maximum benefit from canola stubbles, they should be grazed before any green material that may be present wilts and dies.

- Young sheep should be removed from lupin when the average number of grains available is four or fewer per 0.1m2 (less than 50 kilogram per hectare), or when the amount of ground cover is 50% or less, whichever develops first.

- No lupin variety is totally resistant to the growth of the fungus that produces the toxin responsible for lupinosis.

- Grain poisoning, or lactic acidosis, may occur on any stubbles other than canola though it is least common on lupin and oat stubbles.

- It is essential to have a supply of good quality water that can meet the demand of sheep grazing on stubble paddocks.

There are variations between crops in the lengths of grazing. Because it is not possible to accurately predict the performances of sheep on stubbles, it is important to weigh, or at least condition score, sheep on stubbles regularly (preferably at three weekly intervals) to determine when they need to be shifted or supplemented. A sample of 50 sheep will provide a good indication of the performance of the flock.

As well as measuring the sheep, stubble paddocks should be monitored for the amounts of residual grains. Paddocks should not be grazed after the amount of ground cover declines to 50% or less, because the paddocks are then susceptible to erosion and degradation.

Cereal stubbles

The spilt grain in cereal stubbles contains starch that can cause acidosis if rapidly consumed. Acidosis is caused by the lowering of the pH in the rumen of sheep, leading to part of the microbial population being killed off and a lessened ability by the rumen to process fibrous feed. To minimise the chances of developing acidosis, sheep should be acclimatised to the grain before being put onto ungrazed cereal stubbles.

Spilt cereal grain will not provide enough protein for growing lambs and it is important to feed out some lupin grain as well. This will also help the sheep to better utilise crop residues.

Young sheep on cereal stubbles are unlikely to achieve weight gains of more than 80 grams per head per day but this can be improved by supplementation with 100-150 grams of lupins per head per day. This supplement can be given once a week and can be spread across the paddock using a spreader, or it can be put on a hard surface to avoid contamination. Barley is the most useful cereal stubble and farmers often comment that sheep do better on barley stubbles than on other cereal stubbles. Pastures after barley crops are often much better than those following wheat or oat crops and baled barley stubble has proven to be a good feed source for adult sheep.

Straw quality

The nutritional quality of cereal straw is generally very poor, mainly because of its low digestibility and low nitrogen content and straw alone is seldom able to provide a maintenance diet for sheep. Its main advantage is that it is readily available, cheap roughage that can be used together with other feeds to provide a source of roughage for feeding sheep during summer and autumn.

The digestibility of a feed is the main factor which determines the amount of energy provided by that feed. Concentrates such as barley or lupins are 80-90% digestible and provide a high energy diet, whereas roughages such as straw or hay are generally of lower digestibility (35-55%) and provide less energy. Protein is also an essential component of any diet and different classes of stock have varying nutritional demands for protein. Demands for protein are high during late pregnancy and during lactation and high wool growth rates can only be achieved with a high protein diet. Lupin seeds are about 30% protein and are, therefore, a particularly important source of supplementary protein. Straw, however, contains less than 4-5% protein and an additional source of protein is generally needed with straw diets.

The variations in digestibility between different parts of wheat straw show that the leaf blade and sheath in the stubble have a digestibility of about 59%, whereas the stem material is only 29% digestible. The proportion of leaf material compared with stem is low and sheep preferentially graze the leaf material. Rain during summer and autumn can significantly reduce the digestibility of the stubble, mainly through leaching out the soluble or digestible components of the straw. The nitrogen content of grazed stubbles is also too low to sustain adequate microbial growth in the rumen. This may restrict digestion of dietary fibre and with it the sheep's ability to digest the roughage diet efficiently. An alternative to leaving stubbles in the paddock is to conserve the straw in bales for use later in summer or autumn, when grazing feed supplies are low in quality and quantity.

Stubbles grown in wet areas will be of lower quality than those from drier areas, particularly late in the season when rain may have reduced digestibility further. Farmers should monitor the performance of sheep throughout summer and autumn, either by weighing them or by condition scoring, to provide feeding strategies that will prevent unwanted losses of bodyweight or condition.

Lupin stubbles

Between 150-250 kilograms (kg) of seed per hectare usually remains on the ground after harvest. In fact, rates of 300-400kg per hectare are common. Lupin seed makes excellent sheep feed and this fallen seed may be enough for between one and three months grazing (depending on the stocking rate, development of lupinosis, risk of wind erosion and rainfall).

Typically, weaner sheep show rapid weight gain and wool growth in the first few weeks of grazing stubbles, then reduced gain and weight loss as the seed is used. High seed intakes and rapid growth generally occur during early grazing regardless of stocking rate. However, heavy stocking means that the seed is used up fast, the rapid growth period is short and the weaners lose weight sooner than if stubbles are grazed at lower rates.

Lupin stubbles can be grazed with good gains in weight by about 10 weaners per hectare for up to two months if there are good levels of grain available. Stocking can be higher than 10 weaners per hectare where farmers want to use the lupin stubble early in summer to prevent storms ruining its feed value. Therefore, stocking rates of up to 20 weaners per hectare are more common where summer rain is likely. Good weight gains can be achieved at these higher stocking rates, but the grazing time will be shorter.

As a rough guide, sheep tend to gain weight when there is more than 50kg of lupin seed per hectare (ha) in the stubble and lose weight below this. Generally, four Gungurru seeds in 0.1m2 is equivalent to about 50kg/ha. When seed falls below 50kg/ha, early signs of lupinosis often develop. (Lupinosis is a disease which affects livestock that eat dead lupin stems colonised by the fungus Phomopsis leptostromiformis. The fungus produces toxins, called phomopsins, in warm moist conditions. When consumed, the phomopsins damage the liver which can result in the animal becoming jaundiced.)

Weaner sheep on lupin stubbles, and probably other high protein stubbles, will not travel much more than 600-800 metres from the water supply to graze. This may result in parts of large paddocks being overgrazed and developing the potential to erode. There is also the possibility of stock developing lupinosis. The distant parts of the paddock may have feed that is barely used so multiple or movable water troughs will allow large paddocks to be grazed more evenly.

Canola stubbles

If canola stubbles contain green leaf and stem material, they will provide high quality feed that is most beneficial to young stock and ewes being flushed for mating. It is common for ewes to be joined on canola stubbles.

Canola stubbles should be grazed before the green material wilts and the plant dies. Because of their high palatability, green canola stubbles will be grazed out quickly and rates of weight gain will decline once the green material has been eaten. Weight gain of stock on dead, brown canola stubble will be no better than that on cereal stubbles, that is, less than 100 grams per head per day.

Stubble material and soil erosion

Sheep eat large amounts of stubble materials, especially when little seed is left. Many of the smaller fragments, such as shattered leaves, are trodden into the soil and wasted. Thus, 3-5 tonnes (t) per hectare (ha) of stubble present at the start of grazing is typically reduced to 1-2t/ha when sheep are removed.

According to soil experts, about 1.5t of material per hectare (150 grams per square metre) is needed to protect soils and minimise the risk of soil erosion. This equates to lupin stubble covering about 40% of the ground. Those with stock need to consider how much feed is available and, with their current stock numbers, whether it will last over the autumn feed gap without reducing groundcover to less than the critical 50%.

Reducing ground cover below this exponentially increases the risk of erosion. Selling stock early can reduce grazing pressure and therefore reduce the likelihood of overgrazing and subsequent soil erosion. If groundcover is getting low and selling is not an option, remaining stock should be held in paddocks with gravelly-surfaced soils, since these are less prone to erosion than trampled and loose sandy or clayey soil.

Loosened soil is only protected from the wind by plant cover that is still attached to the ground. When cover in a paddock is reduced below 50% and the paddock is exposed to winds of 30 kilometres per hour or more, loosened soil starts to move and become sorted. The fine fraction, made up of clay, organic material and nutrients, are lifted and transported out of the paddock as dust and the coarse sand is left behind in the paddock or on fence lines. A vast majority of soil nutrients are stored in the top few centimetres of soil. If the surface 10 millimetres (mm) of soil is sorted by wind, the nutrient-rich dust will be removed, leaving the coarse material behind. Experiments have shown that this can result in a 25% yield reduction for the following crop. If cover is marginal now, then despite removing stock, there remains the risk that further decomposition will result in insufficient ground cover to prevent erosion in autumn next year.

Keep in mind that plants begin decomposing naturally once they die and that sunlight and rain both increase the rate of decomposition.

Water

It is essential to have a supply of good quality water that can meet the demand of sheep grazing on stubble paddocks. Depending on the weather, the feed type and the salt content of the water, weaners can drink up to seven litres per day and adults more than this. Water troughs in stubble paddocks need to be cleaned regularly to encourage sheep to drink enough water so that their performances aren’t affected.

Mineral and trace element supplements

Cereal grains are low in sodium and calcium so sheep grazed on these stubbles for long periods may have an inadequate intake of these essential minerals. However, there is not a lot of evidence that sheep on cereal stubbles suffer any illness or reduced performance specifically because of sodium or calcium deficiencies.

Many farmers provide loose mineral mixes or blocks in case sheep require some mineral or trace element. Provision of salt may assist in the prevention of urinary calculi and ice plant poisoning.

Various trace elements are included in most commercial mineral mixes but there are no proven benefits of using them. The levels of inclusion of the minerals are low enough to ensure there is no risk of poisoning but if sheep are truly deficient in one of the trace elements, the inclusion rate and intake may be inadequate to correct the deficiency. If trace element deficiency is suspected, seek professional advice on its diagnosis and the most effective means of treatment.

Urea supplementation, via block licks, loose mineral mixes or molasses based licks, has not been shown to be commercially helpful when sheep have access to adequate roughage and grain but inadequate protein. The response to urea supplementation is variable and unpredictable. Supplementation with lupins, or other grain legumes, is a more reliable way to raise dietary protein levels.

Health issues

The risk of lupinosis occurring in sheep grazing lupin stubbles is increased:

- with increasing the time after harvest before sheep are put onto the stubble

- as the amount of lupin seed available declines (particularly below about 50kg/ha)

- if the sheep have no prior experience of eating lupin seed

- following significant rainfall (about 10mm)

- with varieties that are more susceptible to the fungus responsible for the disease (such as Danja). No lupin variety is totally resistant to the growth of the fungus that produces the toxin responsible for lupinosis.

Waterbelly (urinary calculi) in rams and wethers has a number of causes. It occurs most commonly in summer and autumn when many sheep are grazing cereal stubbles. Continuous provision of salt, as a loose mix or in blocks, may aid in the prevention of waterbelly by promoting increased water intake, resulting in more dilute urine.

Health problems in sheep grazing canola stubble in Western Australia (WA) have been rare but farmers should be aware of the following potential problems:

- A small number of WA farmers have reported that sheep on green canola stubble produced a profuse, foul-smelling scour.

- Two WA farms experienced sheep deaths on canola stubble, which subsequently were found to be due to lesser loosestrife poisoning. This plant prefers wet to waterlogged areas.

- Brassicas in general, including canola, can cause nitrate poisoning, pulmonary emphysema and haemolytic anaemia in stock. These conditions have occurred occasionally in sheep in eastern Australia, but not in WA.

Ice plant poisoning generally occurs within a few days after sheep are put into a new stubble paddock, particularly cereal stubbles. The sheep seek out and avidly eat the dead dry plant, perhaps because of its salty taste. Continuous provision of plain salt, in a loose mix or blocks, may satisfy any craving for salt and reduce the likelihood that sheep will eat ice plant.

Grain poisoning, or lactic acidosis, may occur on any stubbles other than canola, though it is least common on lupin and oat stubbles. The risk of acidosis is increased:

- if the sheep have not previously been eating the grain

- if there are heaps of spilt grain or considerable amounts of unharvested grain

- if the sheep are hungry on entry to the paddock.

Other diseases that may occur in sheep that are grazing stubbles include polioencephalomalacia (polio), enterotoxemia (pulpy kidney), annual ryegrass toxicity, scabby mouth, pink eye and caltrop poisoning. These diseases do not have a particular association with any type of stubble and may also occur in sheep in other situations.

Grazing dry standing crops

Grazing standing dry crops is an effective way of providing good quality feed to sheep (especially weaners). These crops provide an easy to eat food source in a clean grazing environment with few grass seeds.

These crops can be:

- oats (dwarf preferably) — safe and cheap to grow and feed (fail safe)

- peas — excellent for fattening sheep but not so good for growing

- lupins — good feed but be aware of lupinosis

- mixtures of the above can be good but are more complex to grow.

Standing oats are the most reliable and possibly the cheapest crop to use. For each tonne in the paddock you should be able to graze at least 10 lambs for the whole of the summer — that is from just before all the crop is ripe (the best time to introduce sheep) until the break of the season. Dwarf oats tend to keep much of the grain in the head and provide a perfect feed for the weaners. If summer rain causes germination, the green pick will only last a short time. After that they might be thin but will tend not to die. Peas can be added for better feed value but they tend to fail every second year because of frost, pea weevil, native budworms or black stem rot.

Other tips:

- Dwarf oats have more palatable straw and do not ‘spook’ the sheep as much — they can see around and use the whole paddock.

- With a tall crop, make roads through to water etc (this can be done by dragging a log).

- A low cost crop can be a bit ‘dirty’ especially if the paddock is going back to pasture.

- A forage crop can be used to undersow pastures.

- There appears to be no strong evidence for saving some of the paddock until later. That is there is no evidence of better liveweights at the end of summer.

(source: Sheep – the simple guide)