Observing the life cycle of snails in vineyards

Introduction

A 12 month study observing brown garden snail (Cornu aspersum [Muller, 1774] Helicidae) activity within a Margaret River vineyard was recently completed. The aim was to determine the reproductive state of the population over the year by measuring albumen gland and shell size of individuals. This complements the snail baiting demonstration article published in the December 2021 edition of the Wine Industry Newsletter, that demonstrated the efficacy of different snail bait products.

Background

Brown garden snails can lay up to six batches (Bezemer & Knight 2001) (30-120 eggs) per year and the breeding activities happen most frequently in warm and moist conditions (Dekle, et al 2003). Snail eggs can hatch within 10 days or up to three weeks (Crowell 1984), depending on temperature (Dekle, et al 2003). Brown garden snails tend to reach sexual maturity one to two years from hatching but if conditions are highly favourable can be shortened to six months (Crowell 1984).

The albumen gland in snails relates to the animal's breeding viability. It produces a nutritive secretion onto fertilised eggs and consequently will increase in size before a snail lays eggs (Baker 1988). Contrary to this, the lack of gland development indicates inactive egg production (Baker 1988).

Twenty large brown garden snails (shell width 15mm - 31mm) were collected from an untreated vineyard block located in Margaret River each month (March 2021 to February 2022), submerged in water and preserved in a 70% ethanol solution prior to dissection. Dissection of individuals was to determine peak reproductive activity, thus the best timing for snail management. Shell width and albumen gland length were measured using methods established by Baker (1988).

Results

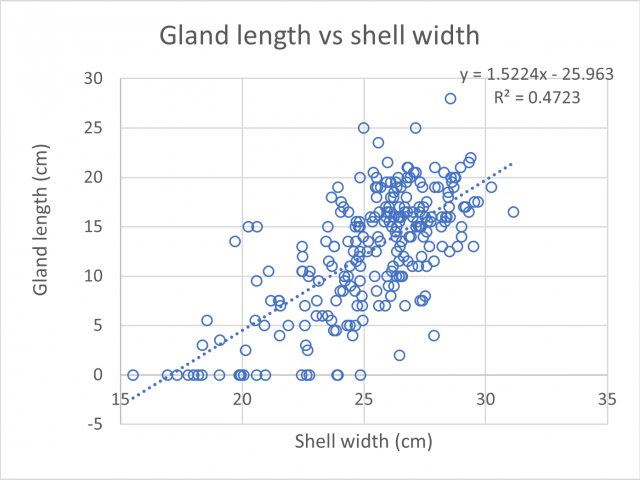

There was a positive relationship between shell width and albumen gland length (Figure 1), meaning during this period of observations it was found that the bigger the snail the larger the gland, indicating large individuals are able to reproduce. In contrast, the shell widths of individuals without a detected albumen gland were all under 25mm.

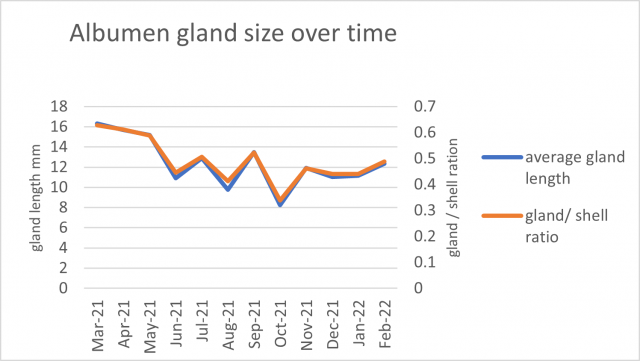

The albumen gland length and its ratio to shell width was greatest in March 2021, followed by a decrease until October before increasing again (Figure 2). The March peak indicates the greatest number of individuals were laying eggs at that time. The average size of the dissected brown garden snails for each period was relatively consistent. It was noted during collection that individuals >25mm (large) in diameter were more difficult to locate in June, July and August compared to smaller snails.

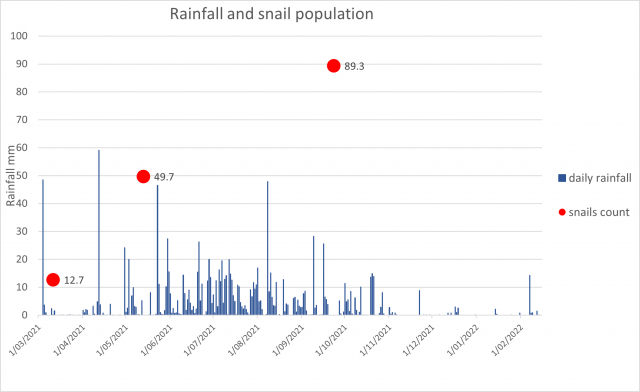

Population data (snails from a single panel within a row) combined with daily rainfall data demonstrates a clear increase in numbers from March (12.6 snails per panel) to September (89.3 snails per panel) which correlates with increases in rain events and rainfall accumulation.

Seasonal observations

Brown garden snails were observed actively laying eggs in the beginning of March (2021). Observed egg laying coincided with a significant rainfall event. Greater populations of ‘small’ active snails were noted in winter, compared to other periods of the year. Most brown garden snails were located on vine trunks in winter with the larger specimens noted to be in an aestivation (dormancy) phase.

In spring, populations tended to move into the vine canopy. Increased variability in size was also visually observed in the population during the spring period.

During summer, aestivating brown garden snails were predominately observed in the ground cover beneath the vines. Interestingly these aestivating individuals upon dissection were found to have large albumen glands, leading to the assumption that they could opportunistically reactivate and commence egg laying under favourable conditions.

Discussion

The size of the brown garden snail albumen gland was greatest in March. However, an enlarged albumen gland was present in most larger brown garden snails ( >25mm) throughout the year, which indicates that adults are able to lay eggs when favourable conditions occur (i.e. high moisture levels). Initial results from complimentary research in South Australian orchards and vineyards support these findings.

Within the vineyard, observations of egg laying in March and increases in visible populations in September may suggest shorter development periods when conditions are wet. Results suggest 2021 was a favourable year for brown garden snails to increase populations at the Margaret River vineyard.

Conclusion

Brown garden snails are opportunistic breeders, whose populations can increase rapidly when conditions are suitable. Without timely and effective baiting, snail populations can significantly increase and become a major management issue causing damage to buds early in the season, defoliating vines throughout the season and contaminating fruit at harvest. Regular monitoring, timely baiting (when snails are active and before laying eggs) and adequate application rates are important to suppress snail populations and to avoid heavy infestations.

Due to the limitations of this study; being from a single site, a single year and no replicates, further research is required to advance the understanding of snail biology in WA vineyards and investigate the opportunities for new management strategies.

For more information on this work, contact Yu-Yi Liao, Technical Officer or Richard Fennessy, Research Scientist.

Acknowledgements

This activity is funded via the Wine Australia Regional Program which is administered by Wines of WA. Support from Mike Sleegers at Cowaramup Agencies and AHA Viticulture in providing access to a site and bait products is also greatly appreciated. Technical advice and support were received from DPIRD staff Svetlana Micic (Entomologist) and Andrew van Burgel (Applied Statistician). Dr Michael Nash and Dr. Sally Foletta are thanked for their input and review of this article.

Reference

Baker, G.H. 1988, 'The Life-History, Population Dynamics and Polymorphism of Cernuella-Virgata' (Mollusca, Helicidae)' Aust J Zool, 1988, 36, pp. 497–512, viewed 18 May 2022.

Bezemer, T.M. & Knight, K.J. 2001, 'Unpredictable responses of garden snail (Helix aspersa) populations to climate change' viewed 23 May 2022.

Crowell, H.H. 1984, ‘The brown garden snail’, Ornamentals Northwest Archives , Jan.-Feb.-Mar., Vol. 8, Issue 1, pp.11-13, viewed 12 May 2022.

Dekle, G.W. & Fasulo, T.R. 2003, ‘Brown garden snail’, University of Florida, Department of Entomology and Nematology, Available viewed 24 May 2022.

Growers to be on the look out for snail pest

Green snail, Cornu apertus (syn. Cantareus apertus, Helix aperta) is a serious pest and has the potential to cause crop losses, mainly in leafy vegetables, cereal crops, pasture grasses and native plants. It can also become a major nuisance pest in agricultural settings as they can breed very quickly, with up to 1000 young snails found per square metre.

Green snail is native to Southern Europe and North Africa and has been established in the Perth metropolitan area since the 1980s. Green snail is a declared pest under section 22 of the Biosecurity and Agriculture Management Act 2007, and landholders are required to report and control the pest on their properties.

Mature green snails have an olive-green shell and white flesh, sometimes with a darker coloured foot. They are intermediate in size; between the smaller vineyard snail and white Italian snail, and the larger common brown garden snail.

The damage caused by green snail is similar to that of the common garden snail – young snails feeding on surfaces of leaves often only penetrate shallowly leaving a 'windowpane effect’, while older snails eat holes in the leaves and may reduce them to veins only.

During the dry summer months (November–March) the snails burrow underground and lie in a dormant state. Following autumn and winter rains the snails become active, with eggs laid in the soil from May–August and young snails appearing in early winter.

Reducing the spread of green snail will help to protect Western Australia’s agricultural industries.

Because snails are proficient hitchhikers:

- Avoid moving snails from infested to clean areas on farm machinery and vehicles

- clean and remove snails from harvest bins

- avoid moving soil, plants and plant material from infested areas to uninfested areas without close inspection to remove any snails.

Confirmed distribution sites in Western Australia include the Perth Metropolitan area, Dunsborough, Capel, Albany and Esperance, with a newly confirmed detection in Kendenup, in the Great Southern wine region. More information can be found on the webpage Green Snail: declared pest.

It is important that suspect infestations are reported. Early detection and reporting of this pest will help protect Western Australian horticultural and agricultural industries.

If you suspect green snail, please contact the Pest and Disease Information Service (PaDIS) on 1800 084 881 or go to the MyPestGuide™ web pages to download the free MyPestGuide™ Reporter app, or make a MyPestGuide™ online report.

DPIRD's record harvest

The DPIRD wine team consisting of Research Scientist Richard Fennessy and Technical Officer Yu-Yi Liao are all smiles after completing their biggest harvest, with hardly an empty vessel left in the wine laboratory at DPIRD's Bunbury office.

The harvest started with a parcel of Margaret River Chardonnay picked on 16 February and the last parcels of Great Southern Shiraz were picked on 20 April.

This year, two projects required winemaking components which involved 73 separate parcels (comprising of 1563kg of fruit) and over 150 individual ferments ranging from 2L to 19L.

The two projects are summarised below.

Understanding the intricacies of provenance in Western Australian wine regions

This project aims to build on previous and upcoming works investigating how the variability of the elements (geology, soil and climate) can impact wine attributes within the Margaret River and Great Southern wine regions. The varieties of focus are Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon in Margaret River and Shiraz and Riesling in the Great Southern as these are ‘hero’ varieties for their respective regions.

The DPIRD team harvested 12 Riesling sites across four subregions and nine Shiraz sites across three subregions in the Great Southern. For Margaret River, 19 Chardonnay and 19 Cabernet sites were harvested. Each parcel was approximately 20kg and picked at a predetermined Baumé specification.

For this project, the team travelled to Margaret River 11 times to harvest sites which equated to around 3000kms travelled. Additionally, seven trips to the Great Southern were undertaken tallying over 5300kms.

The wines from this work will be bottled by August and used for sensory assessment and chemical analysis.

Demonstrating how clonal selection can influence Cabernet Sauvignon wine quality

In 2019 a block of mature Cabernet Sauvignon (clone SA126) in Margaret River (located at Howard Park Wines) was grafted over to 14 different clones and selections as part of a Wine Australia nationally funded project.

This is the second consecutive harvest for this activity which also featured for the first time recordings of key phenological stages, berry weights, bunch weights, bunch compaction, bunch numbers per vine and vine yield. The parcels were harvested on two separate picks, one week apart.

The wines will also be bottled by August and presented at industry wine tasting workshops for producers to gain first-hand insight into how these clones and selections performed.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the Provenance project is received via the Wine Export Growth Partnership of which Wines of WA is a partner. The Cabernet clone activity is funded via the Wine Australia Regional Program (administered by Wines of WA).

2021/22 weather snapshots

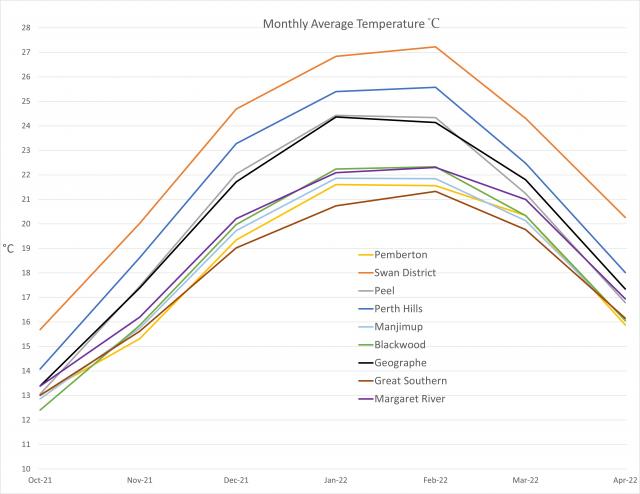

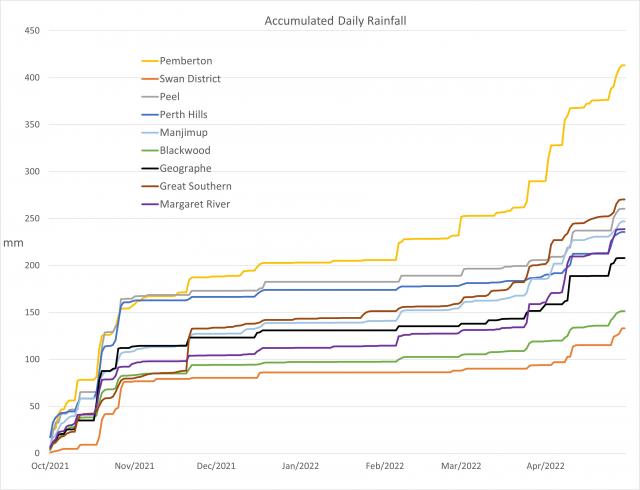

With the 2021-22 wine grape harvest now complete, DPIRD Technical Officer Yu-Yi Liao has collated climatic data for each of WA’s nine wine regions. This provides an illustrated insight into the characteristics of the season (October to April) at a macro level for the regions.

The data displayed in the following graphs was accessed via DPIRD’s weather station and radar webpage and the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM).

Figure 1 shows data collected from the BoM Millendon weather station (site number 9281) to represent the Swan District region. The region recorded 133mm over the growing season, with little rain during the ripening period (December - February).

Three stations were used to represent the Perth Hills, being BoM station Bickley (site number 9240) and DPIRD stations Lesmurdie Testbed and Glen Eagle in Figure 2. Perth Hills accumulated 2338 GDD units compared to the 2688 recorded in the neighbouring Swan District and received 236mm of rain during the season.

Peel’s data in Figure 3 is sourced from BoM Dwellingup weather station (site number 9538).

DPIRD’s stations Capel, Donnybrook and Dardanup 2 were compiled to represent Geographe in Figure 4. Over the season 208mm of rainfall was recorded, the majority of which fell in the months of October, November and April.

Figure 5 illustrated Margaret River’s season with data from the DBCA-A Portable station and DPIRD’s units Vasse, Wilyabrup, Margaret River, Rosa Brook and Karridale. In April there were seven days where daily rainfall was recorded above 5mm, the total over the season was 239mm and total GDD for the period was 1877.

Blackwood Valley is shown in Figure 6 with data sourced from BoM Bridgetown station (number 9617), DBCA station Styles Tower and DPIRD station Nannup. Blackwood Valley recorded the second lowest rainfall during the season at 152mm and similar GDD as Manjimup and Pemberton at 1789.

The BoM station at Manjmup (site number 9573) and DPIRD’s Manjimup HRS station provided data to represent the growing season at Manjimup in Figure 7. Manjimup recorded 1761 GDD units and 247mm of rainfall during the season.

DPIRD Pemberton station was the only station used to produce Figure 8, seasons rainfall was the highest of all the regions at 413mm and 1726 accumulated GDD's.

Acknowledging the size and diversity of the Great Southern wine region, all subregions were combined to produce Figure 9. Stations used were Albany Airport (9741) and Rocky Gully Town (9661) of which are both BoM stations, Water Corporation station Quickup Dam and DPIRD stations Denmark, Mt Barker, Stirlings South, Frankland North and Frankland. Accumulated totals for GDD were 1682 and 270mm rainfall.

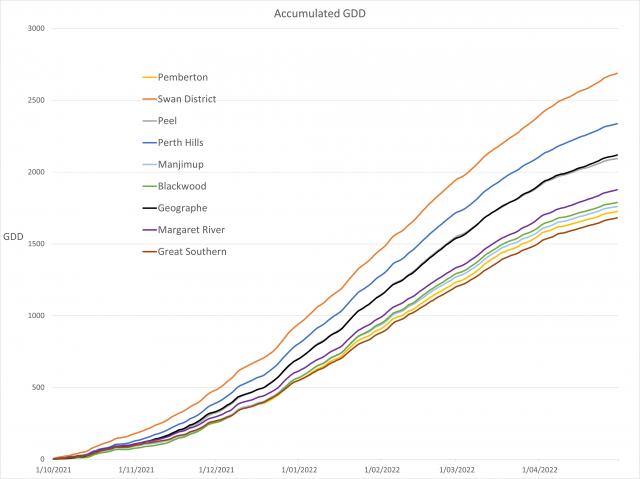

Figure 10 shows the comparative accumulated Growing Degree Days (GDD) for all regions calculated using the Winkler Index with a base of 10°C.

Monthly average temperature is shown in Figure 11. The Swan District as expected, shows a clear separation from the other regions being the hottest of WA’s wine regions. Another obvious grouping is Margaret River, Blackwood Valley, Manjimup, Pemberton and Great Southern at the lower range of monthly mean temperatures across the growing season.

Pemberton is clearly separated in Figure 12 from the other regions in terms of accumulated rainfall over the growing season. This is attributed to a number of daily rain events between February and April exceeding 15mm.

Online tools to describe your climate and soils

The internet is a big place with overwhelming amounts of information, so wine producers can be excused for not being aware of the online datasets they can freely access to describe the climate and soils of their vineyards and localities.

This article aims to highlight a few of these resources.

DPIRD weather stations and radar

This online tool visually displays weather station locations operated by state (DPIRD, DBCA and DFES) and federal government (BoM) agencies. Clicking on the stations provides access to live and historic climatic data. These datasets can be illustrated in graphs, in tables and exported as csv files.

If a vineyard is not near a weather station, clicking on a location anywhere on the map will produce a ‘virtual station’ calculated via an algorithm using data from nearby stations.

Accessing this information on a smart device is available through an app downloadable from Apple Store and Google Play.

Historic climate data from SILO

SILO is a database hosted by Queensland Government Department of Environment and Science containing Australian climate data from 1889 to present. It provides daily meteorological datasets for a range of climate variables in ready-to-use formats suitable for biophysical modelling, research and climate applications.

This site provides up to 10 years of daily or monthly summaries for rainfall, temperature and humidity on a 5km grid.

This site is a valuable source of raw data for modelling and similar activities but not as user-friendly as DPIRD weather.

NRInfo (natural resource information) for Western Australia

DPIRD's NRInfo is a source of natural resource maps and data derived from databases maintained by DPIRD and other government agencies including Landgate, Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage, Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety, Department of Water and Environmental Regulation, Environmental Protection Authority and Geoscience Australia.

This is a powerful and complex tool providing information on:

- Property and cadastre boundaries

- soil-landscapes, land systems, land capability, land qualities and data confidence.

- hydrology (natural drainage lines and surface water catchments, hydrozones for groundwater trend and salinity risk assessment)

- native vegetation (type, pre-European extent, current extent, interim biogeographic regions of Australia).

To fully utilize this tool, users are recommended to first read about the key features.

To demonstrate an excellent feature that can help producers understand in depth the soil properties of an area of interest:

- Zoom into the map to the area of interest or simply search for an address

- select on the top right hand menu ‘Soil – Landscape Mapping’

- click on menu option ‘Soil Landscape Mapping – Best Available'

- move the cursor to the area on the map of interest and click to reveal a summary report

- a report of proportion of soil types and a detailed technical report is now accessible.

Capital investment grant available to wine producers

The Value Add Investment Grants (VAIG) Program supports agriculture, food and beverage businesses to invest in the expansion or relocation of their value adding and manufacturing operations in WA.

The VAIG is a major competitive grant program of the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD), which is designed to build resilience within the agribusiness, food and beverage value adding industries and reduce WA’s reliance on imported products.

As part of the State's broader economic development and recovery post-pandemic, VAIG Round Two aims to strengthen and diversify the WA economy by supporting investments in new manufacturing capability which result in reducing WA’s reliance on imported products, supports business growth, fosters innovation and creates jobs.

This stream provides funds to eligible applicants for the implementation of capital investment projects to expand, diversify or relocate their value adding and processing operations in WA.

Capital investment funding assistance may be available for new investment or bringing forward planned investment projects in existing businesses that involve value adding post harvest or production.

Up to $6 million is available for individual grants of $250 000 to $750 000. Recipients must provide at least $1 of cash co-contribution for every $1 of funding (1:1) received.

Applying for funding is a two-stage process:

- Stage One is an open Expression of Interest process (EOI) allowing businesses to submit a short project summary. No funding will be awarded at this stage. Projects will be assessed and those considered to have high potential will be invited to submit a detailed grant application in Stage Two. EOI Applications open 9am on Wednesday 27 April 2022.

- Stage Two will be a closed, invite-only grant process for the successful projects from Stage One. It will be a competitive process with all applications assessed on their merits by an independent assessment panel.

EOI Applications open 9am (AWST) Wednesday 27 April 2022 and will close 5pm (AWST) Wednesday 22 June 2022.

Further details on the Value Add Investment Grants and specifically the Capital Investment Stream is available on the DPIRD website.

Future events

Australian Wine Industry Technical Conference

The 18th AWITC and WineTech Exhibition will be held 26-29 June 2022 in Adelaide, South Australia. The program will cover the topics of supply and demand outlook, social licence, market trends, sustainability, innovation, vineyard health and biodiversity and the latest research and technologies.

There will also be 38 workshops covering business/marketing, engineering/packaging, health/regulatory, sensory/consumer, viticulture and winemaking.

The AWITC also incorporates the Australian Grape and Wine Outlook Conference.

More information and registrations can be found at https://awitc.com.au/.

SIMINOT&SIRCH regional pruning workshops

Funded by the Wine Australia Regional Program, these pruning workshops will feature Mia Fischer of international pruning specialists SIMONIT&SIRCH.

Mia will be providing an overview of the importance of pruning, utilising the SIMONIT&SIRCH pruning methodology and how it can be used to ensure vine longevity and productivity.

The workshop will also feature a Q&A session and a vineyard walk where possible.

- Swan Valley – 20 June, 8.30am – 11.45am at Nikola Estate, 148 Dale Rd, Middle Swan

- Great Southern – 21 June, 9am to 1pm at West Cape Howe (Art House), 14923 Muir Hwy, Mt Barker

- Margaret River – 23 June, 8am to 12.30pm at Vasse Felix (Barrel Hall), 71 Tom Culity Dr, Wilyabrup

RSVP to Yu-Yi Liao noting the regional workshop attending.

Garden weevil webinar

The program for this event is still to be developed but will feature South African speakers to present an insight into recent research projects using biological control agents and some common management techniques used by local viticulturists. Local speakers will also present on various trials of innovative products from this past season.

In early July details will be circulated to each regional association when available.

Pruning and vine health for vineyard longevity

Mia Fischer from SIMONIT&SIRCH and Mark Sosnowski from SARDI, together with the AWRI have developed a full-day workshop on winter pruning. This workshop will focus on the latest research and best-practice guidelines for maintaining the long-term vine health, productivity and economic viability of vineyards. The workshop includes an interactive in-field demonstration where participants can discuss challenges specific to their region and receive expert advice to address these challenges.

This is an interactive workshop that is best suited to practitioners who value good pruning practices and trunk disease management. It is aimed at practising viticulturists and is limited to a maximum of 25 participants per session to ensure an intensive learning experience.

Cost: $495 per person, including GST

Registration is required to secure a place in the course. Book early to avoid disappointment.

9 August, 8.15am to 4.30pm at Xanadu Wines, 316 Boodjidup Rd, Margaret River